In mid-May, Playkot hosted the global launch of its new Spring Valley game. By June, its business metrics had reached excellent values: the percentage of those paying was 7.7%, and the retention of the first day for organics was 41%. We talked about the history of Spring Valley and the specifics of its development with the producers of the game — Evgeny Smirnov and Konstantin Popov.

Chapter 1. Getting to know the team and the place of the game in the company’s strategy

Alexander Semenov, App2Top.ru : Hello. Tell us a little about yourself at the beginning. How long have you been in Playkot?

Zhenya Smirnov

Zhenya Smirnov: Hello. I’ve been with the company for eight years. He started his career with his own small startups for social networks. Then I got a job at Playkot as a programmer, in a few years I grew up to be a producer of the SuperCity project, which has been the flagship of the company for a long time.

Kostya Popov

Kostya Popov: I’ve been with the company for three years. I also started working on SuperCity.

And how did the story of Spring Valley begin?

Zhenya: It started about three years ago. I was still working on SuperCity at the time. The co-producer and I set a record for the project’s revenue and significantly changed the approach to conducting LiveOps in the game. We can say that with us, SuperCity has pumped up a lot. Sasha Pavlov (CEO of Playkot — editor’s note), seeing this, asked if I wanted to make a new game.

The team and I were just sketching a new title. So, of course, I said, “Yes, I do.” We made a pitch based on a ready-made concept, got the green light for its development and… off she went. We’ve been doing Spring Valley for three years. Now we have finally reached the release.

You just mentioned that you had a co-producer when working on SuperCity. There are twice as many of you at Spring Valley, too. How did it happen?

Zhenya: Historically, our producers work in pairs.

Each team in the company has a high degree of independence, and this leads to the fact that the producer needs to be responsible for a wide range of issues independently. Therefore, we have a practice that there are two producers at the helm of the project.

Successful businesses also often have two founders — one about operational management, the second about strategic management.

Two producers immediately start working on the project?

Kostya: Not always. In our case, when Zhenya left to work on Spring Valley, I picked up his business at SuperCity so that the team could scale further and show cool results.

A year later, Zhenya came to me and said: “Help is needed here,” and I joined the Spring Valley development.

Zhenya: Kostya had already set up the operating part of SuperCity by that time and could safely transfer the cases.

Which of the producers is responsible for what in the work on Spring Valley?

Zhenya: On our project, Kostya is more responsible for production, I am more responsible for the product. But at the same time, we cannot say that we are completely isolated, there are many intersections in our work.

Kostya: It’s difficult to combine everything in one person. Everyone has stronger traits and weaker ones, they need to be balanced.

In general, it is important to understand that at Playkot we rely on strong leads in each direction. Everyone in the market understands this role differently. In our case, a lead is a mini—director of its direction. He hires a team, provides processes, and is responsible for the overall result. Therefore, there is no such thing that we, as producers, look into every corner.

By the way, I was surprised to learn that Playkot is bringing Spring Valley to the market. It seemed to me that Playkot specializes in midcore.

Kostya: Many people often associate Playkot with midcore due to the fact that Age of Magic is the main mobile hit of the company. But we do not believe that we have exclusively midcore expertise.

Zhenya: We have two main directions in our company: midcore, in which we create games designed for a male audience, and casual, focused on women 35+.

We are going to have two conditionally independent streams that we want to pay equal attention to so that they can effectively coexist within the company. We want to work for two audiences at the same time. And we are preparing another project in the midcore genre, a mobile shooter.

The task of Spring Valley is just to strengthen the casual direction?

Zhenya: Yes.

In the history of the company, the largest leap in revenue with access to the international market was made by the casual SuperCity on Facebook.

We also had social games for the male audience — “Line of Fire“, “Titans“, “Knights: Battle of Heroes“. These were very significant projects, they were appreciated by the audience, but SuperCity was and remains far ahead in terms of revenue. The game is still in the top 20 highest-grossing Facebook games. And we continue to actively support it.

We tried to repeat the success of SuperCity on mobile devices. However, on a new platform for itself, the game could not achieve the results of the web version.

After that, we focused on the midcore Age of Magic. It was a breakthrough — the game overtook all our social games in terms of revenue, became a hit.

Today, on the basis of the experience gained thanks to Age of Magic, we are trying to achieve cool results in casual mobile.

Sounds like a plan. But, probably, when you first started it, when you took up the implementation of Spring Valley, were there any concerns?

Kostya: We were afraid that we took up the game in this genre too late. There were more and more similar titles on the market. We were haunted by the feeling that we need to move faster, that the longer we work on the game, the harder it will be at launch.

Zhenya: Since the team that launched the project had no experience in creating a game from scratch, they were afraid that it might not work out, that we would move too slowly, that we would not be able to scale the game by the time of release.

How did you overcome these fears?

Zhenya: They came from the fears themselves. Yes, on the one hand, the team was launching a new game for the first time. But on the other hand, we had a very cool experience working on SuperCity. While working on it, we learned how to create new layers of gameplay due to the quantity, quality and variety of LiveOps mechanics.

We understood that this was our strong point, that with such experience behind us, we would be able to make a game on a good engine, with modern graphics and a good plot.

Chapter 2. The specifics of the niche and metrics of the game

Games like Spring Valley are usually attributed to the adventure genre. This happens because they consistently fall into the corresponding subcategory in the App Store and Google Play. What do you call this genre yourself?

Zhenya: We talked a lot with the guys from Vizor who made Klondike, so we have established their terminology. We call this genre expeditions.

Within it, there is a metagame (farm) in which you do useful actions, spend resources from the expedition, this gives you a certain sense of progress. And there is a research mechanic that creates something like an interactive movie: you spend energy, find resources and interesting objects, produce something and get progress on the plot.

The word “adventure” would also fit as a definition, if we abstract from the fact that there are a lot of games in this genre in the App Store or Google Play, not all of which relate to what we are talking about.

At the concept stage, the game was called, by the way, Adventures. In memory of this, the names of team chats in Slack and space in Confluence have been preserved.

The origins of the genre go back to the days of social games for Facebook. Now one of the main players here is Vizor. What kind of niche do you see for yourself in terms of saturation and competitiveness?

Zhenya: There are already quite a lot of games in this genre, so the competition will be hot.

Our task within this niche is to attract the maximum number of players due to a wide setting and getting into the audience, and then increase LTV to top values through the development of additional mechanics for both LiveOps and new layers of gameplay.

We also see it as our task to tell simple good stories about the relationships of characters with whom the audience will be able to associate themselves.

Suddenly.

Zhenya: Yes. We came to this by working a long distance on SuperCity. A product aimed at women is any story through the prism of the characters’ relationships. For example, if these are detectives, then the murders in them are the background, the main thing is how the characters interact. We see this as our main niche. We will be working here, looking for new settings and stories.

But the narrative itself is a tool that allows you to tell anything. It is important to leave enough room for flexibility here: if we suddenly want to talk about a love triangle or a trip to Mars, the plot should allow us to fit it all in. If we don’t do one continuous story, then it’s less likely that we will get written off and become boring.

By the way, what about the positioning of the project? Now the game, judging by the visual, is served almost like a classic farm, rather than an expedition (when marketing the latter, there is always an emphasis on adventure). Aren’t you afraid of confusion?

Zhenya: What was my original idea?

The female audience of casual games is quite conservative and does not like something radically new. She wants the same thing, but different.

I wanted the project to look like something familiar to the audience: “Yeah, it’s something similar, I’m not afraid of it, I’ll try.”

After installation, after the first sessions, they would see that it was something else. However, by this point, the game should tighten them so that they will continue to play.

Plus positioning is a fairly flexible thing. We can experiment with what we serve in creatives, promo materials, on the page, in the store. If we realize that the focus of the adventure works better, we will logically change the positioning. We can experiment and look for growth points.

If we compare with merge and match niches, as well as with classic farms/builders, how much easier is the expedition segment today in terms of attracting, retaining and monetization?

Zhenya: It is quite possible that in merge games the price for installation is lower. We don’t know, because we don’t have a very high expertise in puzzles. We focus here on the fact that we have expertise in farms and builders, so as the first new project that our team is doing, we decided to rely on this.

If we talk about match-games, there is so much competition there that it is unwise for us to go there now.

But at the same time, all these genres and their projects generally compete for about the same audience? Or is there any fundamental difference between the audiences of these genres?

Zhenya: Yes, the intersection of audiences is probably quite high. Another thing is that in more farming games, such as Township, there is a slightly more hardcore casual audience. There you need to monitor the order board, the limit in the warehouse, think a little more.

Our game is a little simpler. Our genre is not as niche, but also not as wide as match-3.

Have you done research on the volume of this niche? How much do such games earn on average? What is the cost of targeted traffic here?

Zhenya: Now there are three leaders in the niche:

- Family Island, which earns $12 million a month;

- “Klondike“, which earns about $8 million a month;

- Family Farm Adventure, which is now actively growing and earns about $6 million.

According to the cost of targeted traffic, we are guided that we will reach the cost of attracting a paying user to the USA on Android at $ 150.

We don’t look at pure CPI, because there are different channels, they perform differently. We focus on the indicators of the cost of attracting the payer.

Which business metrics are considered good in the niche?

Zhenya: If we talk about retention — R1 ≥ 40%, R7 ≥ 20%, R30 ≥ 10% is a good result, ≥ 7% is normal.

By metrics in the States: 7% of those paying for 30 days is a good indicator.

Since we are talking about the business metrics of the genre, what about Spring Valley?

Zhenya: Now we have the retention of the first and seventh days above the feasts for which we requested data, and a good percentage of those paying is 7.7%.

We also have 50% R1 for paid traffic. For organic matter: R1 — 41%, R7 – 19%, R20 — 9%.

By the way, our metrics are open to teams. To find out how the project is doing, you don’t need to go somewhere into the statistics system – everything is visible on dashboards in the office. People see the result of their efforts in graphs and figures, better understand how their work affects the overall result.

Kostya: Yes, we try to take people into the team who will be interested not just in doing tasks, but also to immerse themselves both in their field and in adjacent ones, and take responsibility for the result.

Now, according to App Magic, the project has reached a daily revenue of $7000 per day. This is about $210 thousand a month. What values are you planning to reach?

Kostya: Now we actually earn more than App Magic says. Advertising monetization gives us another plus 25% of our income. We expected to get less and were pleased with the good result, but so far we are wary of it.

We have heard about the market average of 10-15%. Perhaps the high proportion of advertising monetization does not mean that we have done it very well, but that we can still shake monetization.

Zhenya: In June, we plan to earn about $400 thousand with advertising monetization. In general, this year we plan to reach a million per month, but two factors will affect the results further.

Firstly, how quickly we will be able to grow LTV.

Secondly, at what speed traffic will become more expensive, how quickly we will eat up a loyal audience.

Both the first and the second are still difficult to predict.

On the way to the result, we primarily focus on things that we can measure, on data. We have a fancy dashboard system, which I have already mentioned. The game is decomposed into systems and subsystems by which we evaluate the performance.

But in parallel with this, there is a creative part that is difficult to measure, and here we are guided by the principle of “do it normally, it will be fine.”

Of course, we cannot do without a subjective expert assessment. You often watch some TV series, and on the sixth season you realize that it has slipped. When you realized this, you still watch a couple of episodes by inertia and fall off. It is difficult to measure such things in a moment, but in the long term it is possible to maintain the integrity of the vision: there is a visionary, a product producer who knows what should get to the audience, and within this framework, the guys in the team have a fairly high degree of freedom in terms of what plots to do and what objects to draw.

Chapter 3. Features of game design, content volumes and personnel issue

In this genre, I have always failed to understand the following: I usually see the need to introduce a large number of additional mechanics when they go as an add-on for high-level players. Immediately, they all fall out on the player at once (and the farm, and match-3, and the research part), which increases both the volume of the tutorial and the entry threshold. Is there a problem here?

Zhenya: I don’t see a big problem here. We have a good retention of the first day, everything is fine with onboarding.

Over time, we will build even more complex mechanics for high-level players, but they will be located a little later in life time, so as not to overload the player with mechanics (you need to enter them when the player has already mastered the basic ones).

Now the expedition genre itself is an interactive story, to which some mechanics (or mechanics) are attached from above. And the future of the genre depends on how much it can evolve, how interesting a story can be told with the help of new mechanics, how much it will be possible to change the meta, which is now the farm.

Is it necessary to change the meta at all?

Zhenya: The farm is also boring, plus it is not suitable for all kinds of stories. This is also a field for experiments.

That is, when developing Spring Valley, have you decided not to experiment much with the genre yet?

Zhenya: Why is that? We made a character editor, gave the player the opportunity to customize his character. It seems that none of the competitors have done this before us.

The character editor has slightly complicated the issue of plot presentation. However, we thought it would have a good effect on retention. If you’ve spent 15 minutes trying to create your character, you’ve already become a little attached to the game.

We also introduced the mechanics of relationships with the characters of the game.

A large number of mechanics requires a huge amount of content. What size of team did he require at the stage of active development (before softlonch) and now, at the stage of operation (after the world release)?

Zhenya: On the one hand, in terms of content, it’s easier for us to create value for the player than, for example, in battlers. Everything is quite linear with us: you make new levels, the players play them, the players feel good, they pay you money. But the flip side is that you need to raise a very large team of artists and designers.

We went global with a team of 45 people. But we understand that for a project of this level we need 100 people. Now this is a really serious challenge for us. We have to actively build up the team.

You just mentioned that it’s easier for a player to create values in a casual game, and which game is easier to play before release — casual or midcore?

Zhenya: In casual games, the balance is simpler, the system itself is simpler, but there is a nuance — you need to produce content. As I mentioned just above, there is a lot of content.

All games are content-dependent to one degree or another. However, in more hardcore games, working with content is a little easier. You give the player some item that improves some metrics, the player is hacked in PvP, everyone is happy. Here the main difficulty is to adjust the balance.

Casual games are more difficult to conduct before the release. There is no history of increasing metrics, there is no PvP. Here, first of all, you need to export a large amount of content on a regular basis, and for this you need a huge team.

Here you say that you need to “export” a large amount of content. This means that when developing casual games, artists, game designers, and screenwriters are needed in large numbers. And as for programmers?

Zhenya: We have only two developers in our team. From experience, we knew that the high speed of movement is compensated by the fact that there is a huge clumsy layer of legacy, which is hard to work with, which sometimes drags projects to the bottom.

Therefore, we have two client developers, and game designers and other participants in the process can do everything else using the tools that we have put into the project to the maximum.

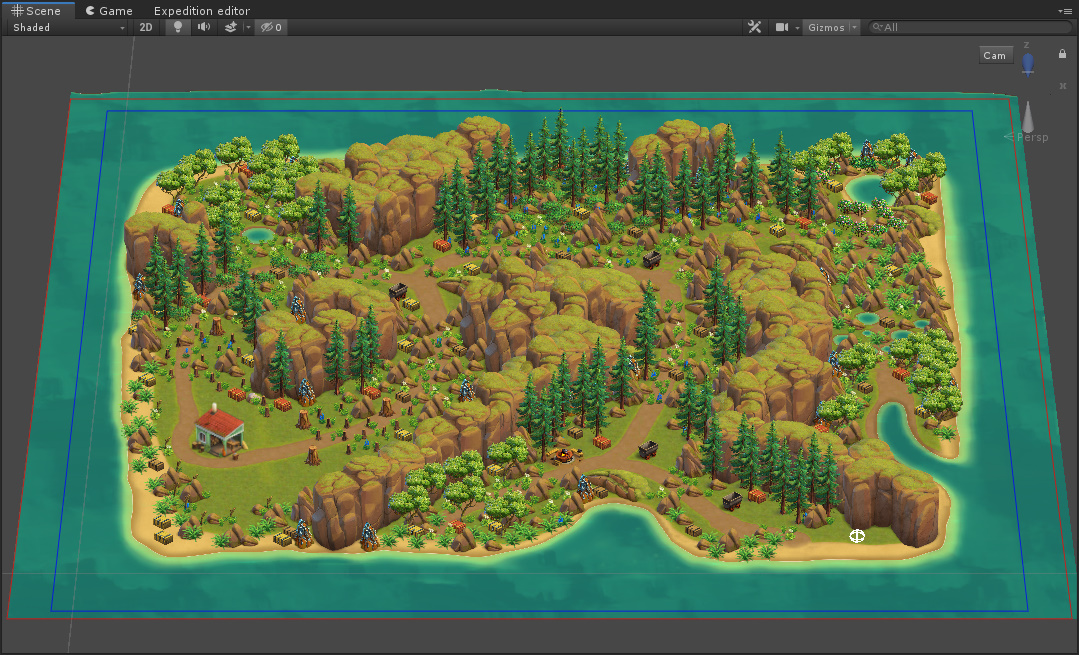

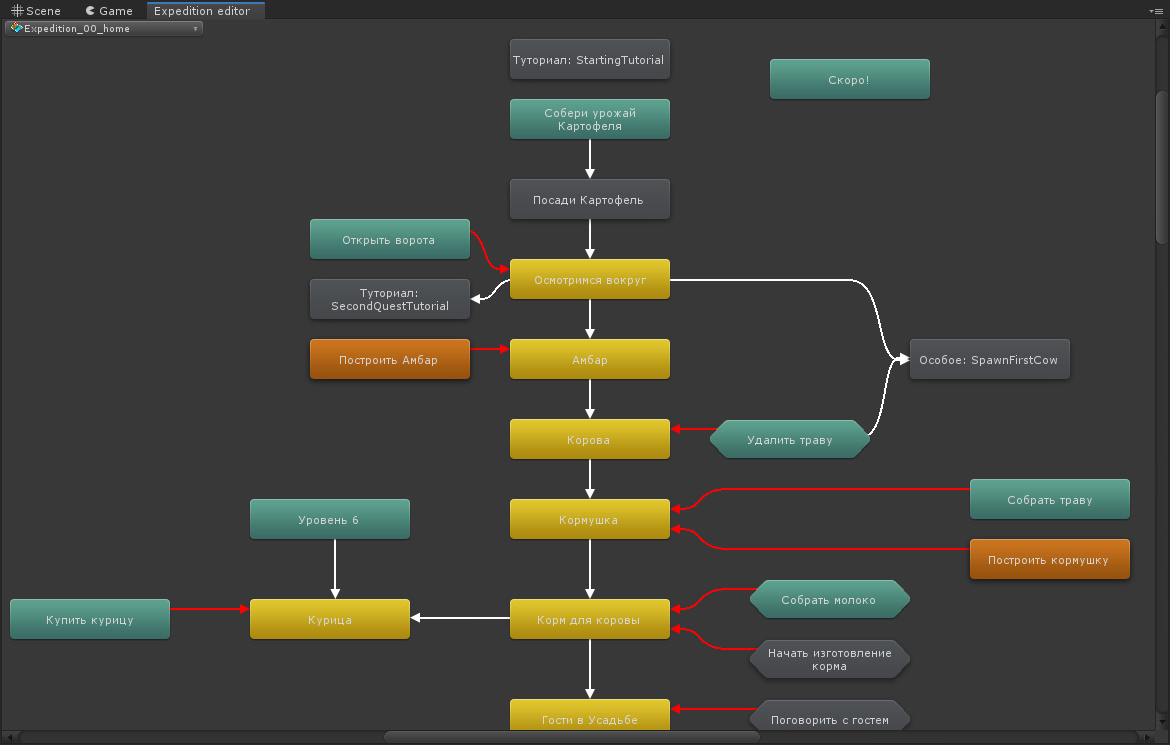

Kostya: The task of the developer is not to do the whole feature on the disdock, but to make tools with which the game designer can customize the game himself. Therefore, our game designers are such t-shape guys: they write a disdoc, balance it, and set up the location with the expedition in the editor. There are examples when programming is a little bit.

Screenshot of the location editor with the resources and gifts placed.

Screenshot of the expedition editor. Everything is configured in the editor: from the conditions and the filling of the expedition itself to the localization keys.

And the last question. In the CIS, casual development accounts for 80-90% of the entire industry. Is it possible to say that it is easier to recruit cadres for casual games than for midcore ones?

Zhenya: No, it’s hard for us to hire. It’s about two things. Firstly, we prefer to take people who really want to make games for women. Many are cut off on this. Secondly, we have set a very high bar. When selecting candidates for the team, we have a conversion rate of about 10%.

Kostya: We have such an approach to people: we take only the very cool ones. The people we choose should be ready to take responsibility and make decisions. We try to compensate for this by regularly reviewing salaries based on market research. Twice a year, sometimes more often if there are sharp changes in the market.

Zhenya: But yes, in general, there are really a lot of cadres on the market with experience in casual development.

Thank you for an interesting conversation!

Where to play:

???? Google Play

???? App Store

???? Huawei App Gallery