This material first appeared on the pages of the British edition GamesIndustry.biz . We offer its Russian version.

There is no shortage of lectures on success at GDC, games that have achieved critical acclaim or financial heights. There are much fewer reports at the conference about those projects that failed.

At noon the Tuesday before last, I witnessed a panel in which four developers painfully (but hopefully usefully) recalled the details of their defeats.

Massive Damage CEO Ken Seto started the panel by discussing the Pocket Mobsters game released by his team in the summer of 2013.

Pocket Mobsters

“I think the game sucks to some extent, but this sucks has nuances,” Seto said.

Pocket Mobsters received good support from Apple, and was downloaded about 200 thousand times in the first five months, but the game had a problem, namely retention. The retention rate of the first day was 13% and by the thirtieth it fell to 3%. The game was actually dead,” Seto said.

The head of Massive Damage partly blames a similar situation on the fact that the game was created in the midst of a reshuffle in the company, when the number of employees was halved to about a dozen developers. And at the same time, one of the co-founders, Seto’s brother, left the studio.

The team was hoping to quickly release a hit that would bring cash and get the whole team together again, but it didn’t work out.

In general, the situation looked like this: only “juniors” were responsible for the development of that fastest hit – The Pocket Mobsters, while the rest of the studio was focused on supporting the previous title – Please Stay Calm.

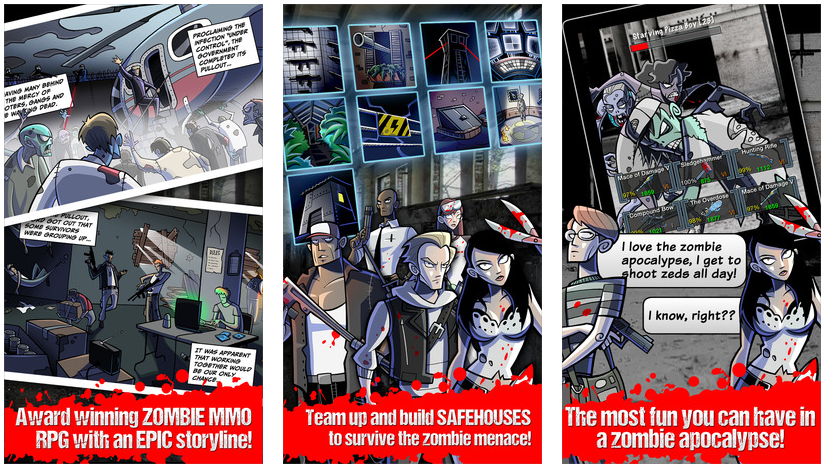

Please Stay Calm

The chosen theme of the game did not meet the needs of the audience for which it was expected. The game had a setting inspired by the TV series “Underground Empire”, but with graphics made in the style of cute pixel art. Seto said they didn’t take into account that the audience of a gangster game might prefer a hardcore visual style to “cute” pixel art.

Plus, the project was created on the basis of the game Please Stay Calm, which was developed in a very specific way. As a result, any change in The Pocket Mobsters required a spaghetti code, which took a lot of time. This may have hurt the game the most, since a ton of features were originally planned, but they simply did not implement them, because it would take too much time within the framework of the situation.

“We decided to close the project, and this was probably the most difficult decision we made, because we all loved it very much,” Seto said.

They warned the players about the closure of the project four months in advance, turned off all IAPs and allowed all paying players to transfer their characters to equivalent strength in Please Stay Calm.

One of the biggest lessons Seto highlighted for himself was that you shouldn’t fall in love with your own ideas. If something doesn’t work, cut quickly and move on.

Seto also noted that you can’t learn from your mistakes if you don’t want to take responsibility for yourself.

The number of studio employees is now 10 people, but the developers have plans for two new games. One of them – Halcyon 6 – has already started a Kickstarter campaign.

Halcyon 6

The co-founder and CEO of Vancouver East Side Games, Joshua Nilson, was next, he talked about MightyBots. The idea of the game was to create a fighting puzzle game about robots. The secondary goal was to promote the company’s technology and create a hit in three months. The deadlines shifted immediately, because the development team could not decide whether it was doing basic mechanics in real time or step-by-step.

Mighty Bots: Fighting Robots

During the production of the project, the team leaders divided the development of the game into six-week cycles, within which the team had to reach milestone or “be killed”.

Neilson stated that it killed morale in the team. The developers also had a feeling because of this that the studio itself had never been engaged in development. This was partly due to the fact that the top initially could not even agree on the key mechanics.

Moreover, after months of development and release on the App Store, the management finally decided to remake the game from realtime to step-by-step. As a result, this led to the departure of the audience from the game.

In the future, Nilson said, he is going to pay more attention to when it is necessary to make decisions about such significant changes that it is better to implement immediately in a new project.

Neilson also admitted that the East Side could have abandoned the project, which would have been a much smarter decision. The development of the game was so difficult that it got to the point that the team had to specifically indicate to the management what and how the project was going wrong.

The good news is that MightyBots was nominated for the Canadian Video Game Award, and also learned a lot about the cost of development, burn rates (the average cost of one employee per month for the company) and tracking. In many studios, the management does not share such information, but in the East Side, all team members have access to it.

The game director of Backflip Studios, Bryan Mashinter, was the next to take the floor to talk about one of his company’s blunders. He began by talking about the importance of expectations and that results are considered unsuccessful if they do not meet these expectations.

“Expectations themselves can be confusing,” said Mashinter, showing images of movie posters of Star Wars: Episode I and The Matrix Revolutions. Then he showed a poster for Fast & Furious 6, saying that he liked the movie, although he expected the movie to be disgusting, but it turned out to be much better.

Gizmonauts were a “hidden threat” to Backflip Studios. The game is the development of ideas laid down by the team itself in the hit DragonVale. Since the game was the spiritual heir of a very popular project, but had improved graphics and a large number of social mechanics, high hopes were pinned on it.

Gizmonauts

But almost from the very beginning, the game did not go “as it should”. Despite the fact that the projects had similar retention rates on the first day, by the seventh day at Gizmonauts they had slipped to 13% versus 20% at DragonVale. The DAU of the game during the launch was expected to be high, but then decreased. Against the background of DragonVale, the data looked very weak (the DAU of the dragon game remained at a high level for a very long time after the release). Comparing the earnings of the two games was an even more sobering experience.

“I think we made a mistake in our assumptions,” said Mashinter. “We were not able to think outside the box that we ourselves created and.”

Many of Gizmonauts’ design techniques were taken from what worked within DragonVale. But when the soft launch showed weak indicators, the developers did not react properly. They were in love with the things that had previously functioned, and were blindly confident that the game, like its predecessor, would succeed.

They also did not allow the thought that users might not like the setting of the game with cute robots. It turned out that people don’t like robots that much,” said Mashinter, noting that there is not a single game with a robot theme in the Top 200 box office games in the App Store. Since then, Backflip has learned to rely more on A-B testing, to look at data impartially and to bypass robots.

Alex Schwartz from Owlchemy Labs concluded the panel by talking about how working with a publisher (in this case with Sega) didn’t make sense for their game Jack Lumber, in which a lumberjack takes revenge on trees for the death of his grandmother.

Jack Lumber

A team of four people created the game independently on the basis of their own prototype, created in January 2012. They polished the project in April of the same year to take part in Indie MegaBooth, and everything went well for them. The reviews were excellent, and the developers were already going to publish on their own when Sega invited them to become part of the new mobile initiative The Sega Alliance.

It was, recall, 2012, and the App Store was full of paid applications, so Owlchemy made a deal under which Sega had to help her with marketing and would leave the studio IP. The Japanese had only a minimal percentage of income, as well as the rights to publish the game on iOS. These conditions looked quite acceptable.

Anyway, from the moment of launch, the game began to have marketing problems. Sega wrote a press release that Owlchemy completely rewrote because it didn’t match the mood of the game. The same situation was repeated with the key art to the game. In fact, Sega, instead of saving Owlchemy time, on the contrary, spent it.

Despite the favorable reviews at the launch of the iOS version, the game diverged with difficulty.

The developers ported the game to Android and Steam, were included in the Humble Bundle and made versions for Leap Motion, Windows Phone and other platforms. After all, 86% of the money that the game earned was not earned on iOS.

Sega didn’t make catastrophic mistakes, but at the same time it didn’t do anything stunningly right,” Schwartz said. He also noted the transfer of rights to the iOS version back to Owlchemy as a goodwill gesture of the Japanese company. So the partners have no questions left for each other based on the results of cooperation. However, in general, the contract with Sega did not make sense for the studio at the time of its conclusion: the game was already ready and in demand.

The biggest lesson that Schwartz learned from this story is that the studio should have absolute control over the project when it comes to building its own brand.

A source: http://www.gamesindustry.biz