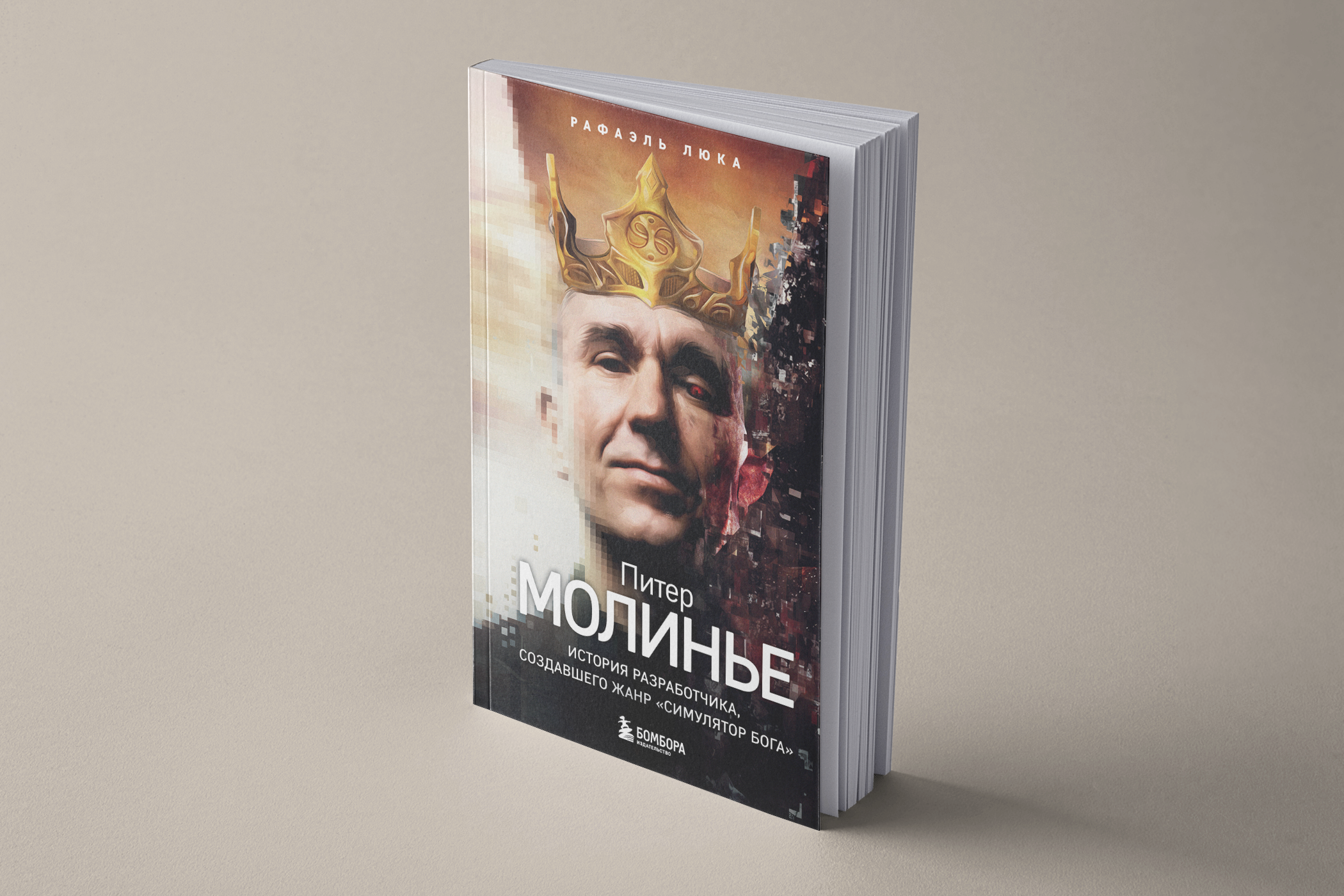

Bombora Publishing house reported that the book “Peter Molyneux appeared on Russian shelves. The story of the developer who created the “god simulator” genre. It is written by the French gaming journalist Raphael Lucas. In it, together with Molyneux himself, he traces the entire path of the game entrepreneur and developer from the first sales to the current work at 22Cans. We publish an excerpt.

POPULOUS (1989, ELECTRONIC ARTS)

The studio received press attention after its Druid II port and the creation of Fusion, but Bullfrog managed to really break into the video game scene only thanks to Populous. Up to this point, the vast majority of wargames or strategies were step-by-step (for example, all SSI products of that time) and used hexagons to build landscapes, but at the same time experienced acute insufficiency in terms of graphic execution. If you don’t like primitive maps and endless menus, games like UMS: The Universal Military Simulator would hardly attract your attention…

Although Peter insists that there was nothing deliberate in the development of Populous, we can still praise the team’s ability to make the right decisions in time: an isometric projection that put the player in the position of a divine observer, both detached and able to interact with this world; the AI of the population, which constantly strives to build new buildings, selecting more and more lands of the opposing people; management simplified to a dozen understandable icons, which made the game accessible to more people; using the keyboard and mouse to move around the map and interact directly with the world; the original theme of religious war.

Compared to other games in a similar genre on the market, Populous is a living, teeming, swarming universe: everything in it swarms, moves, reacts to the slightest click. Perhaps it was this immediate interaction with the environment that made Peter, Glenn and Kevin’s game so successful. In 1989, the influence of Dungeon Master was already felt — a role-playing game that revolutionized the entire industry and led it into an era of more ergonomic and responsive games. The developers, who scattered the controls all over the keyboard and sometimes even accompanied the titles with multi-page instructions, suddenly began to listen to the lessons of Doug Bell: “Why not use a mouse in the game?”. Like Populous, Dungeon Master relied on a limited number of player interactions with the environment, but each of them left an indelible impression. Any gamer of that time remembers the first time he pressed a button on the screen, and the descending grille fell directly on the mummy, crushing it with its weight. This simple physical action was enough to feel yourself in the center of events — the immersion was complete. The same applies to the blocks of land, which can be added and removed on the fly in Populous with a simple click.

A year later, Ultima VI: The False Prophet, which was also influenced by Dungeon Master, allowed players to pick up any items in the game and drag them into inventory. For the past fifteen years, players have been praising the “grip” mechanics from Ico and Shadow of the Colossus, the undisputed masterpieces of Fumito Ueda. In fact, all this is a narrative and emotional development of what Dungeon Master has already put into practice in 1986: press the left mouse button to grab an item in the world or inventory, then hold the button and move the mouse to move this object… Populous evokes similar feelings when you sink enemy units, removing all the blocks under their feet, or level the territory, creating ideal lands for the settlement and expansion of your people. The player is in the center of events and influences this world in the most radical way, sometimes deadly for its inhabitants, and all this happens thanks to the simplest mouse clicks — just like Peter with a stick at the ready once judged the anthills near the swamp in the village of Cove.

Another reason for Populous’ success is its isometric appearance. Such a performance was not new, many developers have been using isometry since the mid-1980s, in particular Ultimate Play the Game, the first studio of the founders of Rare. Knight Lore (1984), Alien 8 (1985), Nightshade (1985), Gunfright (1986) or Pentagram (1986) used all the features of isometry in the action-adventure genre. Later, RPG, action-RPG, strategy and other games used an isometric view at a distance from the scene and the main character (or heroes) with skill-demanding viewing angles, referring us to the idea of controlling the avatar as a toy. In isometric 3D, there is no immersion into the body of the character, unlike the camera from the first or third person, he is also a rear view. It is logical to assume that such a perspective is preferable for tactical games (T-RPG, management, CRPG), when clarity of actions is of paramount importance, and the characters act only as pawns that need to be moved around the field. Much less often, this type was used in adventure games and action-RPG of the 1990s.

In Populous, the camera returns the player to his divine position, from where he can control his people only indirectly, by creating symbols and/or a chosen anointed one, whom everyone will follow, landscape changes that open up new opportunities for people to settle further, bringing disasters to the opposing people, and much more. It is this double perspective, simultaneously immersing in the game universe and moving away from its events (we influence the world physically, but do not control these little men), that made the theme of divinity and the term god game itself so relevant. In fact, Populous is not so much a strategy, a game about managing a settlement or an unconscious criticism of religion (after all, we kill, light fires and sacrifice ourselves for our own god when he is not busy drowning entire populations), as a project about infection with ideas, about memetics: every god (or religion) spreads influence on the constantly changing world is like a virus in the body, constantly reproducing itself, and at the same time each believer (for obvious technical reasons) is identical to the other.

Finally, the little men who came to life in this game will come to life again in Powermonger, Syndicate and Fable.

“I’ve always found this scale of interaction fascinating: with a community, not with an individual. Probably, all this is based on events that I vividly remember. The first of them is a story from a horror collection that I read as a teenager. I don’t remember the author’s name, but it was about a man who locked tiny people in a cage and watched them every day, torturing them physically and psychologically. And at the very end they took revenge on him. The second event was the game Little Computer People (1985, Activision). There was a person who could control commands from the keyboard. If the player didn’t interact with him, he just lived his routine life, and I found the process fascinating. And the third inspiration was an episode of the TV series “Beyond the Possible” called “Sand Kings”. In it, the scientist discovered a race of intelligent insects, then placed them in a glass container and began to observe them. Insects, in turn, began to consider him their god, erect statues to him, and eventually escaped, killing him. Obviously, the topic of influencing the whole world has always existed outside of games. It’s so exciting to realize that you are outside such a universe and can destroy it, improve it, transform it. Then I thought, “What happens if I take a stick and start poking around in an anthill?” What would have happened if that scientist hadn’t been so cruel to insects in the episode “Sand Kings”?”

The press was not mistaken then. In the 19th issue of Ace in April 1988, Andy Smith recommends the Populous game to everyone, even shoot ’em up fans, it turned out to be so dynamic and accessible. In Zzap!64 (48th issue, April 1988), two reviewers even take on the guise of God and the Devil, sharing an enthusiastic opinion about Populous… In general, the grades are excellent everywhere.

Populous is a masterpiece.

“Three weeks after the release of Populous, the phone rang in Bullfrog’s office: It was David Gardner from EA, who remains my friend to this day. He said, “I’m just calling to let you know that Populous sales are going very well. But we have an emergency here: copies of the game are running out, we need to print more floppy disks…”Then David uttered an incredible phrase: “What does it feel like to be a millionaire?”He didn’t mention at the time that it would be another nine months before we would see at least some money for Populous from Electronic Arts. At that moment, everything changed, and truly strange things began to happen.”

For example, there was a call from the Japanese company Imagineer. “On the other end, someone told me: “We really like Populous. We are currently in the UK, so our president could come to your office — we want to talk about your game. You know, Populous could be a huge success in Japan,” and I kind of agreed. And then their president came to that awful little room where our studio was, and while he was climbing the stairs to the top floor, Kat saw him. She grabbed a broom and began to beat him to drive him out of the building. She thought the man wanted to attack her. So he called us and said, “I’m standing at the door and I can’t get in because of some crazy woman,” so we went down to get him ourselves. But he was the president of a company with a billion-dollar turnover, he had personal drivers and all that. Such crazy events began to happen to us one after another.”

The frog is growing, growing, growing… and Peter, getting more and more immersed in his work, hires new people.

“We hired Paul McLaughlin, who I still work with at 22Cans — he’s right in front of me right now! He is one of the best artists in the industry. And Sean Cooper came to us as a teenager: he was unemployed and was undergoing a youth training program. Populous proved to be incredibly successful. We didn’t make the millions that David Gardner promised, but it was still a huge success. For the most part, the furor was associated with the press: I remember the first time I was shown on TV, and then there were a lot of interviews and articles in magazines. We were invited to meetings with publishers all over the world, and we even went to some game developers. During those nine months, I was writing code for Powermonger, doing press relations, hiring more people… But we were still in the same office, so we had to tear down the wall to expand it. And then, unfortunately, Kat died. The apartment she lived in was vacated, and we moved in. It was a crazy time, I felt it very keenly. We were all in a state of incredible tension and had no idea how to behave further. It was then that I first saw Bullfrog as a company, and not as a group of friends sitting surrounded by cigarette packs and cans of Cola.”

Peter (Pan) has finally found his island, his paradise, his Neverland and his lost children. But our Peter, like Peter Pan, could not be called such an exemplary character: he was selfish and showed all the emotions inherent in a person, sometimes getting carried away unnecessarily. Our Peter was remembered for tantrums, objects that he threw at employees, broken aquariums, impatience and a constant desire to succeed, run a business, sell. He wanted to forget about who he was as a child, forget the horror of school and constantly move from one project to another. Endless work, incessant attempts to fill the soul, to occupy time with something, to catch up with it. But this elusive stream always flows by too fast.

“To make more money, we needed a gorgeous sequel to Populous, so after Powermonger I developed Populous II. But at that time, there was one oddity in the video game industry: the players did not approve of the creation of sequels. They said, “You’re just not creative enough.” The press and gamers didn’t want direct sequels, which seems incredible these days, because now everyone is just talking about creating franchises. So when we finished Populous, neither Glenn nor I, nor anyone else, thought about a sequel. As soon as we managed to release Populous, we immediately started thinking about the next game, which we started when we expanded the staff. We had a teenager named Adrian Moore — alternately a sound engineer (Populous), and then a designer (Framed), with whom, oddly enough, I talked just this morning. Then he was an ordinary fifteen-year-old guy who came to help us develop levels. He was also helped in this by Alex Throwers, who still works in the industry.”

Have you ever heard of Roger Corman, the director and producer of category “B” films, whose filmography literally spreads through the pages of Wikipedia? Under his leadership, Francis Ford Coppola, James Cameron and Martin Scorsese shot their first works, learned this craft, tried their hand at any genre, as long as their films brought at least some money. There is something similar in St. Petersburg – this ability to notice young, often insignificant talents and develop them (while paying them pennies or nothing at all). Bullfrog quickly became a place of attraction for young talents, sometimes even teenagers who have already begun the difficult path of applied development.

Tick-tock, tick-tock. Time passed, filling up with more and more new classes, interviews, lines of code that need to be typed, games that need to be played. And crunch again: Bullfrog existed in a state of constant overwork, in captivity of a hard drug — the very crunch that is so criticized and rightly condemned these days when it comes to, say, CD Projekt (The Witcher series) and its eternal management problems.

“Back then we worked almost all the time because we loved what we were doing. Most of us were about the same age and social background. No one had a girlfriend or a partner, except for Les, who was in a relationship. We had no obligations, no children, nothing like that. Therefore, we were free to do our favorite thing all day long: we worked together, communicated with each other, just hugged the game or laughed at something in it. We didn’t have meetings of the board of directors or the management team that could restrict us and make edits. We were just crazy young people without any framework, and in such conditions, ideas for games came from everyone.”