In June, a new book about game design from the American indie developer Robert Zubek will be on sale. It is called “Elements of Game Design” and is an introductory guide. In it, the author not only explains the theory, but also offers practical exercises. We tell you more about the book and share the first chapter.

“Elements of Game Design” is a manual for those who want to understand the basics of game development. Robert Zubek, the author of the book, worked in such studios as Electronic Arts, Zynga, Three Rings Design.

The head of game design at Nexters, Svyatoslav Torik, called the book a “concentrated guide”, noting that the practical techniques from this manual are a great way to “direct thinking in the right direction.”

Here is the first chapter.

ELEMENTS OF GAME DESIGN

1. Elements

“For a certain period of time we leave ourselves, and when we return, and something expands and strengthens, we feel ourselves changed both intellectually and emotionally. And sometimes… Sometimes we experience things that life would never allow us to experience. This is an invaluable gift.”

Marianne Wolf, “What does immersion in a book do to your brain?“

We all know the feeling of deep and pleasant immersion in a book, a movie, a work of art. We consciously strive to succumb to their charm, to look at the world from a different point of view. Different kinds of art achieve this by different means, but they all share this mysterious power.

As players are well aware, games have such power. Plunging into them, we experience a familiar feeling of transformation — for a certain period of time we leave ourselves and become someone else, experience a different life, are transported to a new world, become participants in a story.

Games also have additional power. In them we get the opportunity to act. We can perform various roles. We become adventurers, discoverers, commanders — not only through experiences, but also through our active actions. We feel what it’s like to be someone else, to act in another world. We learn directly about the consequences of various actions, learning from our own experience how the world works. This is the unique power of games — they allow us not only to observe the world, but also to live in it, act and even change it.

Our task as game designers (and at the same time the topic of this book) sounds like this: how to create such worlds that players will inhabit and interact with?

Design process

By creating a new game, we can already have an idea of some of its main ideas, about what type of game this is, what the player will do in it or how it will look like. But you need to turn these ideas into concrete details of a new game by developing the design from the very beginning. Just as writers prepare to write a book by sketching a plot or characters, so game designers use various methods to prepare for the creation of a game: they plan mechanics and feedback loops, analyze the player’s actions in various circumstances, compare the player’s motivation with the perception of the game, and so on. But the main thing is that we create prototypes and experiment.

In this text, we will talk about a variety of tools and processes used by game designers. Not a single game is born fully formed — they require a certain creative spark, but in addition, technical means and the ability to implement their plans are necessary. In this book, we will focus on the last part, namely on the practical methods used by game designers – such as mental models, process descriptions and ways of thinking, which are especially useful in the process of creating new games.

Games as mechanisms

Games can be viewed from different angles: from the point of view of the plot or scenario, from the point of view of decoration and visual design, from the point of view of cultural analysis, etc. But since at the moment we are most interested in creating gameplay and player interaction with the game, we will take a different approach.

Let’s focus on games as systems with which the player interacts — as mechanisms with which they play. In this case, the word “mechanism” is an abbreviated designation of a dynamic model, an artificial system of rules for interaction, and not some kind of physical structure in the literal sense. It is necessary to emphasize the interactive and dynamic nature of the game: this is a mechanism with its own rules; by checking various possibilities, the player interacts with this mechanism, and the mechanism reacts to the impact and, in turn, forces the player to act further. This alternation of impact and reaction within the rules of the game forms what the player perceives as “gameplay”.

To understand how these mechanisms work, we will take them apart, and in the process we will inevitably begin to distinguish some repetitive patterns and patterns. Among the wide variety of games, there are some common features, common structural elements and similar design solutions. In each original game, they can manifest and combine in their own way. The program is made up of standard building blocks, and although new elements appear over time, many of them have existed for a long time and are well known. When assembled, such a structure allows players to interact with themselves in a specific way and generates a special kind of gameplay.

This way of analyzing and understanding games is not the only one, but it is very useful. Practicing game designers have already identified and identified many common structures and building blocks that are regularly repeated in the practice of game design.

Player-oriented game design

Talking about their profession, game designers adhere to the tacit assumption that games are created in order for players to play them. It sounds like a banality, but not everyone views games in this way. Mathematicians, for example, may consider games as problems to find the optimal solution, ignoring the players.

But we will stick to the key principle that games exist to be played. And because they are created for players,

then we have to take into account the players and their perception from the very beginning. The player should be the starting and central point in the design process.

Player orientation is a fundamental principle of game design. The game is being developed as a source of impressions (experience), as a mechanism for interaction, providing the player with agency (the possibility of active activity) and autonomy. Following this idea, we will consider three elements in the design process: the experience goals set by the designer; the game artifact that will realize these goals; and, most importantly, the player experiencing this experience. All of them are necessary for a dialogue between the designer and the player using gameplay with a conceived design.

So where do we start?

Motivating example: Poker

Let’s use the popular poker game as a practical example to study — consider what elements it consists of. Imagine that we are sitting in a group of friends and playing a game. What parts is this process divided into?

First, let’s highlight the basic structure. There are a number of game elements that participants interact with: cards, chips, a game table and other components that represent the physical aspect of the game. We can consider them objects, or nouns, of the game. Cards and chips are concrete objects, but there are also more abstract elements: the distribution of cards (“hand”), the player’s move, etc. They don’t have to be physical. Online poker consists of the same objects (such as a table), only virtual. In addition, we have rules on what to do with these elements and at what moments. The rules define actions, or verbs, matched with the specified nouns: when to shuffle the cards, how to deal them, how to make an initial bet, how to raise or equalize it, etc. The game begins with some initial game state, and then, thanks to the actions of the players, moves from one state to another. In the case of poker, there are rules that determine the victory of a certain hand, so players can try to achieve a winning state with the help of the cards issued to them.

Starting the game, the participants set all the elements in motion. The dealer shuffles the deck, the participants make initial bets, they are dealt cards. Then the players take turns making their move, analyzing various options: they can equal the previous player’s bet, change some cards for themselves, raise the bet, save, etc. At some point, the combinations of cards in the players’ hands are compared with each other, after which the winner is determined. Then the process starts again. This is the gameplay of the game — analysis, decisions and player interactions. But it is not limited to just game objects. Players calculate the odds and react to the actions of other participants. They bluff and try to force opponents to fold. They can pretend that they have completely different cards on their hands than in reality. Other players are a very important element for many games, and poker is especially famous for being a mixture of elements of strategic thinking and planning with psychological tactics and attempts to predict the actions of opponents.

On top of that, you can talk about what the players are doing and what they are experiencing during the game. Of course, the participants compete with each other, but they also cooperate — for example, creating and destroying temporary alliances. Players risk their money and enjoy the thrill of knowing that they have placed a bet on an uncertain future. They calculate their next steps and enjoy planning their actions. But at the same time, the participants talk and joke, fight for the status of the winner and have a good time in the company. This is the experience of a poker player. Pleasant pastime, socialization, gambling, thinking over strategies, attempts to deceive each other — a combination of strong feelings is quite attractive for many, thanks to which people get great pleasure from this process.

Description of the model

In our analysis of games, we will use the following three levels.

- Players interact with various game objects.

- Interaction with the game and with other players over time forms the gameplay.

- The gameplay generates certain experiences (experiences) and sensations for each player.

In the case of poker, the elements are cards, chips, etc., and players can talk to each other, which is considered one of the acceptable game actions. Based on the rules, participants sit down and begin to deal cards, place bets, equalize or interrupt them, bluff in order to confuse opponents, as well as otherwise interact with each other and with the changing state of the game. This, in turn, allows players to enjoy competing with each other, socializing, counting chips on the table, developing strategies for winning, or just having a conversation and having a good time with friends.

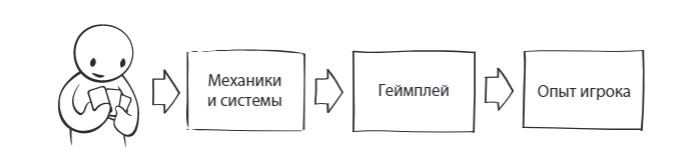

Figure 1.1 shows the interaction between the main objects and actions, the gameplay they produce and the resulting player experience.

These three levels can be given more general names (Figure 1.2).

- Mechanics are game objects and actions that players perform with them. They can be assembled into systems with certain properties.

- Gameplay is the process of players interacting with game mechanics.

- The player’s experience is the subjective feelings of the game participant from the gameplay.

This is our basic model of interaction: players interact with mechanics and systems that generate gameplay perceived by players in the form of subjective sensations. In the following sections, we will describe in more detail how this model can be used to understand the roles of players and designers in shaping such interaction.

This three-part model was developed based on the MDA model (Hunicke, LeBlanc and Zubek, 2004), in which there are three levels. They are called “mechanics”, “dynamics” and “aesthetics” (mechanics, dynamics and aesthetics), although the correspondences between the levels of these two models are not exact. The similarities and differences between them are explained in the “Additional literature” section at the end of the chapter.

Illustration 1.1. Poker example

Figure 1.2. Basic model: mechanics and systems, gameplay, player experience

The role of the designer

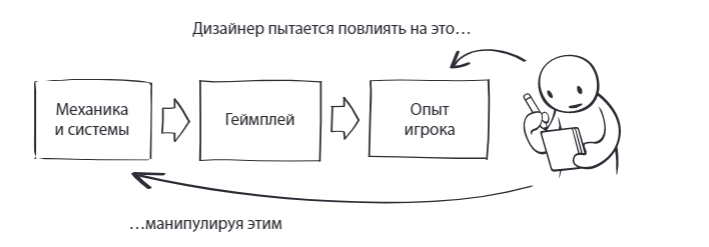

Let’s now imagine ourselves as a designer who wants to create a new game. Usually, a specialist already has some idea of the player’s desires – for example, he wants him to solve some strategic tasks, enjoy narration with a new plot, or realize his fantasies about becoming a different person from another era. The possibilities are almost limitless, but how to put such an experience into practice?

The difficulty is that we are not able to inspire the player with these desires directly. We can only manipulate the specific basic elements (game rules, objects, characters, etc.) that make up the game. We need to create a game artifact that, when used, will help the participant experience the experience we have conceived.

This is a difficult problem of the second order, doubling the distance to the final goal for us. We are creating not just a static object, but a dynamic mechanism that will behave in a certain way, so we can only hope that the player will enjoy such behavior.

Design process

If we consider how the design of something else is being developed – for example, not games, but software or physical objects, then two directions of the process can be distinguished.

- Top-down design: We start with general concepts and goals, then divide them into smaller parts, describe in detail how they work, then divide the parts into even smaller fragments, etc.

- Bottom-up design: We start with the smallest possible elements, and move towards our overall concept. We test what we have created, make sure that it meets our goals, and then gradually build the whole system from small fragments.

In game design, these two approaches look like this.

- When moving from top to bottom, the designer starts with the player’s intended experience and decides how to divide it into several parts. We think about what kind of gameplay can generate such an experience, and then we think about which of the mechanics we know will help create this gameplay.

- When moving from the bottom up, mechanics and systems are first developed that are tested on real players; regular gameplay testing helps to understand what kind of gaming experience it creates.

Figure 1.3. The role of the designer: the development of mechanics and systems to create the intended experience

In practice, these two approaches are not used separately from each other. Pure top-down design is difficult to implement, because when trying to design dynamic systems, it is difficult to predict how they will work when they are offered to players. Pure bottom-up design is exclusively experimental, but if you are not guided by any concept and idea of the player’s experience, then all these experiments will never lead to the creation of anything solid.

Figure 1.4. Two approaches to design: top-down and bottom-up

The solution is to resort to a hybrid, iterative approach, work from both ends, develop plans from the top down, experiment from the bottom up and, most importantly, create prototypes from the earliest stages, regularly testing design ideas and trying to create something solid and coherent based on them. Such a hybrid, iterative process makes game design similar to some of its other types (Brooks, 2010).

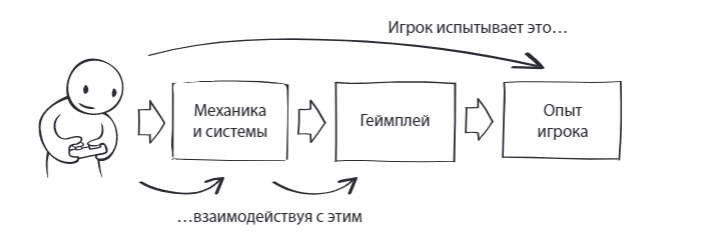

Player Experience

The player views the game from a different perspective than the designer. He doesn’t know what kind of experience we have planned for him, so he starts with specific elements of the game — mechanics, game objects and rules. The player starts the game and starts playing.

The resulting experience is very different. Players can admire fascinating strategic tasks or have a good time exploring the virtual world, or they can experience unpleasant emotions, disappointment or boredom. But all these feelings are generated as a result of passing the game — interaction with various game objects, rules, possibly other participants — at the discretion of the player.

As it has already become clear by this point, the player’s experience is not what the designer intended, but what he implemented. The player knows only what is provided to him — objects, rules, enemies or tasks. The designer’s intentions are immaterial, except when they are expressed in implementation.

There is also some confrontation between the designer’s intentions and the player’s actions. On the one hand, the player plays in a world created by a designer, interacting with mechanics and systems provided to him by a specialist and conceived in a certain way. On the other hand, the player has freedom of action, he has his own ideas about what he wants to do, not necessarily corresponding to the designer’s idea. As a result, only the player can decide what to do, within the rules of the game, he has complete freedom to act as it seems right to him.

The gameplay is the result of the interaction between the player and the designer. Both the specialist and the player contribute to it. The designer sets the framework of experience, and the player acts as he wants — according to the expectations of the specialist or contrary to them. Sometimes such interaction turns out to be successful, and the designer manages to realize the intended experience. In other cases, players find their own ways to shake the designer’s design and turn it into something else that corresponds to their wishes. And sometimes a carefully thought-out design simply collapses, and the whole experience falls to pieces. Such interaction is a dialogue that requires a certain degree of cooperation on both sides, as well as an understanding that there is no single “right” way to play the game.

Figure 1.5. The game experience consists of the player’s interaction with the game

Elements of the game outside of this model

So far, we have described elements such as mechanics, systems, gameplay and player experience that underlie game design. In the following chapters we will cover them in more detail.

But, as any gamer knows, not only these elements provide the pleasure of the game. Of course, they are extremely important, but there are other things that also affect the player’s experience.

Visual design has a huge impact on the perception of the game. It means a whole range of different elements — from the design of the environment (how the game world is presented to the player), the appearance of characters, surroundings and typical objects to the design of such small features as font or detailing of three-dimensional models.

The quality of the user interface and its overall presentation also directly affect the player’s perception. In computer games, they usually talk about “designing the user experience”, although in physical games, the tactile sensation of game objects or the perception of the playing field can also be attributed to the user interface.

The choice of the “setting”, or the context of the game, is closely related to visual perception — the world in which the process unfolds, the role of the player, etc. The way the player perceives his role in the game world naturally affects his feelings about the whole process.

In narrative-based games, the plot plays a very important role. The player’s perception is influenced by such scenario elements as characters and their motivation, the situations in which they find themselves, the development of the plot, as well as more basic aspects — for example, the quality of dialogues.

A huge role in video games is played by music and sound design, music design or soundtracks. In some genres, music and sound design undoubtedly occupy a central position.

Technical design elements are usually hidden from the player, but they have a very big impact on the quality of the gaming experience — for example, the level of AI (artificial intelligence) challenging the player or the types of multiplayer matches available for the platform.

An attempt to map the variety of game elements that collectively affect the player’s impressions and experience is reflected in Figure 1.6.

In this text, we will focus only on the design of mechanics and gameplay and how changes in gameplay affect the player, assuming that “the rest is equally important too.” In other words, in this case we will focus on the aspects of the gaming experience generated by the gameplay. But the overall impression of the game and the overall experience of the player from any particular game is a multifaceted phenomenon, for which gameplay is not the only factor, often not even the main one.

Figure 1.6. Examples of non-gameplay elements that affect the player’s experience

Game Design Practice

Until now, we have used the term “game designer” in a broad sense – to refer to a person who creates game elements, mechanics and systems that generate gameplay and affect the player’s experience. Let’s now consider more precise definitions of the term “game designer” in the practice of the gaming industry.

Game design, system design, content design

In practice, the term “game designer”, as a rule, describes a person whose immediate responsibility is to develop the rules of the game, and then implement them.

This understanding intentionally separates this profession from others, such as a graphic designer focusing on visual design, or a programmer in charge of the architecture of program code and its implementation. And although the player’s experience depends on the contribution of each team member, it is the designers who are responsible for the gameplay, that is, for how the game behaves and how the player interacts with it.

Next, the profession of a game designer is divided into categories.

System designers focus on general mechanics and systems, such as the following.

The rules of the game are based on what “nouns” and “verbs” are.

Battle design — how battles take place in the game, which units participate in them and what weapons are used.

Economy Design — rules on how objects and currency are exchanged.

Content designers focus on individual game objects and actions .

The level design is the specific environment in which the game unfolds.

Character design — what the characters are and what they do.

The design of the world is the environment in which the player makes his way, why it is interesting, etc.

The distinction between system design and content design is sometimes very blurry. As a rule, both are usually handled by the same people. In general, “game design” is the definition of how the game will unfold, thinking through the rules of interactions, but “system design” is a subtype that pays more attention to general rules, and “content design” focuses on more specific places, characters or objects, as well as rules related to these specific elements. As we will see in Chapter 4 “Systems”, when setting up the game and when checking the balance of the general rules and individual elements, you should definitely pay attention to these types.

As for other types of design, such as user interface design or visual, they are not considered “game design” in the industry. Usually the people involved in them are called “artists” because their task is to design, not to develop interactive interaction (although the design of user and graphical interfaces is a more interactive and interdisciplinary direction). Similarly, the design of worlds can be handled by writers who develop the overall plot of the game, invent stories and motivations of characters, etc., but they do not develop the rules of the game concerning the behavior of the world.

Of course, all these roles can be performed by one person at the same time, so in small teams, the lead designer usually does a variety of things that intersect with other areas. A content designer often works together with a visual designer and a story writer, and system designers work closely with programmers.

In this text, we will focus mainly on game design. Content design is a very broad discipline that requires specific knowledge with a great emphasis on styles and genres. You can learn more about it in the books listed in the “Additional Literature” section at the end of the chapter.

Interdisciplinary interaction

Game design is one of the pillars of game development, while other equally important ones are graphics production (visual design) and programming (including architecture design and software development). Development companies often attract specialists from other fields, such as writers or sound designers, as well as professionals from other industries less related to game design, such as business management or marketing.

The division into art, game design and code development is always reflected in the structure of the studio. The organizational structure of projects is often formed vertically in accordance with these disciplines. It makes sense to unite game designers into one group under the guidance of a game director, because this way they will be able to evaluate each other’s work and make useful comments.

At the same time, these roles are often assigned to other specialists. It so happens that in practice, in addition to vertical distribution in work collectives, there is a horizontal division into small interdisciplinary groups. Such working groups bring together representatives

all three disciplines and are engaged in the development of some specific feature of the game from beginning to end. In this text, we will talk mainly about design elements, but it is very important for a game designer to learn how to cooperate with representatives of other disciplines – artists, programmers, marketers, business planners and others.

A brief summary

In this chapter, we have presented a basic model, the basis for further discussion. Its key provisions are as follows.

- Further, games will be considered as “mechanisms” and as systems of rules and principles of interaction that players use and that determine their actions. We will focus on how these mechanisms work and how they can be analyzed.

- This text discusses games on three levels.

• Mechanics — the individual elements that make up the game.

• Gameplay is a dynamic process of interaction with the game by the player.

• Player experience — the player’s subjective impressions of the game. - Mechanics is the most accessible element for analysis. Players interact with the game through mechanics that generate gameplay and determine the specific perception of the player. Game designers may want the player to have some specific impressions, but they cannot directly cause them. Instead, we have to develop mechanics that determine the specific gameplay and affect the impressions of the player interacting with them. But both mechanics and players can act in unpredictable ways. Designers should take this into account whenever possible.

- In practice, game design is divided into system design of general rules, mechanics and systems, and content design, that is, the design of individual specific elements that the player encounters. We will focus on the first type.

- Finally, this text focuses on gameplay, but it should be remembered that other elements of game development also have a huge impact on the player, on his experience and the pleasure he gets from the game. We will talk about the participant’s experience from the point of view of how this process follows from the gameplay.

Based on the three-level model of game design, the chapters of this book consider these levels and are distributed as follows.

- In chapter 2, we start at the top level and look at different types of gaming experience, as well as different ways to analyze it.

- Next, in chapters 3 and 4, we switch to the lower level and consider in detail the mechanics, what they are, how they work and how they form systems together.

- Then, in chapters 5 and 6, we’ll look at the middle level — how mechanics and systems lead to gameplay, how it can be analyzed, and how gameplay determines the player’s experience. These chapters describe a kind of synthesis of the experience conceived by the designer for the player and the mechanics that implement it in practice.

- Finally, in Chapter 7, we switch to the whole process — how designers use the described analytical tools when developing games and creating prototypes, thanks to which the initial idea turns into a working design.

Additional literature

Formal tools

Game designers began to share their experience from the very first days of developing commercial desktop and computer games — describing their methods, analyzing existing games or giving advice on what worked and what didn’t. But as the industry grew in the 1990s, the need grew not just to exchange experience in connection with specific products, but to generalize and document all the experience accumulated by game designers. Perhaps the most famous attempt at such generalization was made in the article “Formal Abstract Design Tools” by Doug Church (Doug Church, 1999), followed by Greg Kostikyan’s response in the form of an article “I have No Words and I Must design” (I Have No Words and I Must Design, Greg Costikyan, 2002). Both articles are available online and are worth reading in their entirety.

MDA

Over the years, various general models of game decomposition and analysis have been developed. One of the most popular is the MDA framework (Hunicke, LeBlanc and Zubek, 2004), which formed the basis of this work. The author of this text is one of the co—authors of the work on the MDA model.

Readers familiar with the MDA concept have probably noticed its similarity to the model described here, because it also describes three aspects of design. In the MDA model, they are called “mechanics”, “dynamics” and “aesthetics”, which is why the model got its name (mechanics, dynamics, aesthetics). This text preserves the division into three parts, as well as the emphasis on the design problem of the highest order, when players and designers have to interact with the game artifact only through its mechanics.

But in this paper, the MDA model is not stated for a number of reasons. The main thing is the striking difference between the terminology of modern design practice and the terminology of the MDA concept. The term “dynamics” is almost never used in practice to describe gameplay, it would make it difficult for readers to communicate with real designers. Similarly, the term “aesthetics” in the MDA concept means “aesthetic impression of interaction with game systems”, but in the game development industry it is used almost exclusively in discussions about visual aesthetics, and not about the gameplay experience of the player. To insist on the terminology of MDA would be a source of confusion.

Secondly, in the MDA model, the concept of “dynamics” is considered too broadly and includes both the analysis of dynamic systems consisting of mechanics and the analysis of the player’s interaction with the game. And although both of these aspects have common roots (they describe behavior), in modern design practice it is considered more convenient to talk about game systems as a separate class of phenomena that differ from gameplay cycles and from gaming experience when interacting with a program.

Finally, the arrangement of the designer and the player described in the MDA model at opposite ends of the chain is idealized and confusing, since in the real iterative design process, the game is approached simultaneously from both sides. I hope that this improved model will help to eliminate some of these shortcomings.

Design Practice

As for design in general, and not just games, an extremely useful book, which is an introduction to design and tells how its choice is determined by psychology, is Norman’s “Design of Everyday Things” (The Design of Everyday Things, Norman, 1988). “The Design of Design” by Brooks (The Design of Design, Brooks, 2010) is also quite an accessible introduction to the general theory of design.

Among the literature devoted to game design, especially content design and the daily work of specialists in this industry, including numerous interviews with professionals, two relatively recently published works stand out: “Game Design Workshop” by Fullerton (Game Design Workshop, Fullerton, 2008) and “Tests for Game Designers” by Brathwaite and Schreiber (Challenges for Game Designers, Brathwaite and Schreiber, 2009).

In addition to gameplay design, game designers should be familiar with the basics of visual design, as it usually greatly affects the impressions of the game and its passage. An excellent introduction to the visual design of games and its impact on gameplay is “Interactive Stories and Video Game Art” by Solarski (Interactive Stories and Video Game Art, Solarski, 2017a) with numerous practical tips and hints.

My manual is devoted to the practice of game design as artifacts and does not pay much attention to the external factors of the gaming industry, games as a means of communication, as narratives or their intersection with broader cultural and social practices. Among the literature devoted to these aspects, the “Rules of the Game” by Salen and Zimmerman (2004) are worthy of mention, especially the third and fourth parts, as well as the collections of essays “First Person” (Wardrip-Fruin and Harrigan, 2004), “Second Person” (Second Person, Wardrip- Fruin and Harrigan, 2007) and “Third Person” (Third Person, Wardrip- Fruin and Harrigan, 2009).

Exercises for individual performance

1.1. Nouns and verbs

Choose a multiplayer game you know and disassemble it in the same way as poker was disassembled in this chapter. It is better to choose a poker-level card or table game that is not too complicated. Answer the following questions.

a. What are the nouns and verbs of this game? What do the players do in it and with what do they perform actions?

b. What is its gameplay? What happens when players start the game? What kinds of activities are they involved in?

Q. How can a player’s experience in this game be described? Does it give pleasure? How does the gameplay affect the impression of the game?

1.2. Elements outside this model

Again, analyze the game that you considered in exercise 1.1. This time, highlight the elements in addition to mechanics and gameplay that affect the impression of it. Make a list of them. What are these elements? For each element in one sentence, describe how it, in your opinion, contributes to the enjoyment of the game.