On October 20, a space western from Alawar was released on Steam. The novelty is called They Always Run. Its unique feature is a hand—drawn visual style. We talked about how it was created with the producer and lead artist of the game Stepan Komarov.

The release trailer for They Always Run

Alexander Semenov, Editor-in-Chief App2Top.ru : Stepan, hi. I’ll start with a traditional question: how long have you been in the industry, what did you do before?

Stepan Komarov

Stepan Komarov, producer and lead artist of They Always Run: Hi, Sasha. I have been in the industry for 15 years. All my previous works were related only to visual style: I was a concept artist, a lead artist, and most of the time I was an art director. I started with casual games, then created the visual part of Distrust and I am not a Monster. On They Always Run, I’m performing as a producer for the first time.

The central program of our conversation is the visual style of the game. However, I suggest starting with a short story about the game. What is They Always Run?

Stepan: This is a story-driven action-scroller.

Sounds complicated.

Stepan: I can rephrase it. This is a story wrapped in an action platformer.

At the head of the corner in They Always Run are:

- the story we want to tell;

- the visual style that we have created and which fits the story and creates the atmosphere of a space western;

- action, which we made dynamic, visually interesting, diverse.

The player controls a three-armed mutant bounty hunter named Aiden. He takes various tasks — orders for bad guys, catches them, delivers them and receives a reward for which you can take upgrades. Slowly, in the course of such work, the main plot and the story of Aiden are revealed.

We tried to make the tasks not of the same type, but interesting and unpredictable in a good way. This is not a set of 10 levels where you reach the boss, catch him, then move on to the next boss, catch, and all over again. We have changed the predictable structure of the game.

What do you mean?

Stepan: For example, opponents may behave differently: a fighter does not want to be caught and will fight, a coward will run away, external forces may interfere in the process of capture…

In other words, within the framework of the plot, do you try to avoid hackneyed techniques and tropes, and at the same time make sure that what is happening affects the nature of the gameplay?

Stepan: You could say that, yes.

Art to They Always Run

Sounds ambitious. How many people are working on the project now?

Stepan: For a project with such ambitions as They Always Run, there are microscopically few of us — there were 10 at the start, now there are 13.

Did the team gather specifically for the project?

Stepan: No. We have been together with the team for a long time, we did Distrust and I am not a Monster. But this is the first time we are doing an action project. Let me remind you, the same Distrust — point & click survivalist, I am not a Monster is a turn—based tactic.

Why did you take up action? Did you get bored doing quiet games?

Stepan: To be honest, we’ve been itching to make a project with direct control for a long time: when you press right and the character runs to the right at the same moment, and not just point him to a point, and he moves there.

This opportunity appeared thanks to the management, who ordered to create the game that we really want ourselves, the main thing is that it should be cool.

What an order!

Stepan: I agree, this is a rarity in the gaming industry, if not nonsense.

The order came and you immediately said that you would make a space western about a three-legged alien?

Stepan: No, of course not. Everything was more complicated. A contest was organized: anyone could present their idea of the game in one paragraph, and the production team considered it.

When the contest was held, we collected more than 100 ideas, looked at them and chose 10, in our opinion, the most successful. Of these, the guys and I conditionally removed the 5 that we definitely don’t want to do. The rest were launched into prototypes — they were of different genres, but almost all with direct control.

It so happened that the idea of our game designer Artemy Naimushin about a game about a space hunter got into this top five. And although the producers chose the games regardless of who the author was, it so happened that the one who came up with the idea eventually began to implement it.

And I myself wanted to make a game about space travel, an action game inspired by the TV series “Firefly” and “Cowboy Bebop“. We can say that the stars have converged.

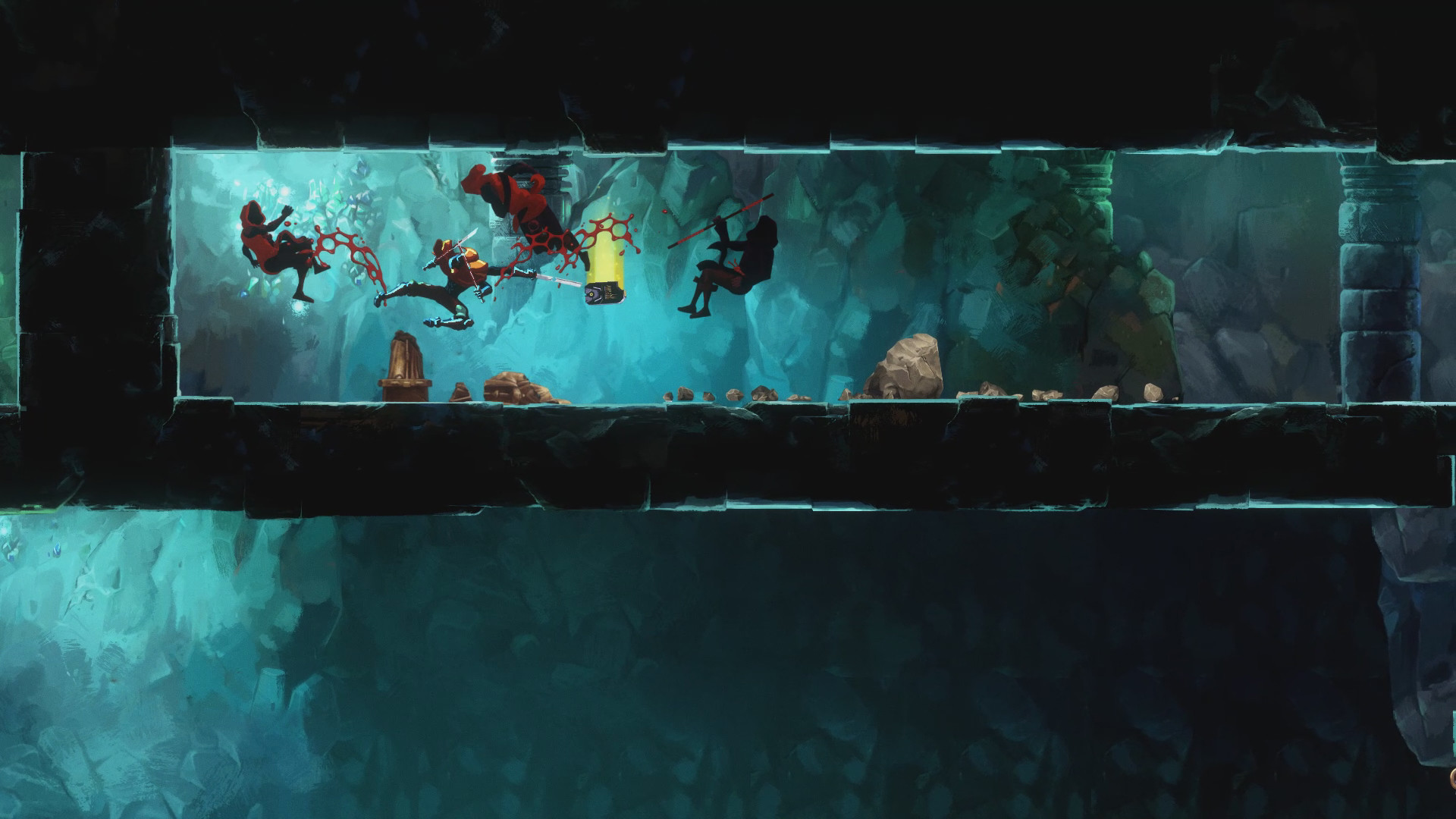

They Always Run

All five were eventually put into production?

Stepan: No.

We first prepared prototypes. Among them, it was necessary to choose one for production.

How did you decide what would go to work, and what would have to be put on the table for now?

Stepan: We cut off games that can not be done qualitatively by ten.

It hurt. I wanted to do everything.

They refused not immediately, looked, weighed everything.

The most difficult decision had to be made when there were two projects left. We liked them equally, we had already done some amount of work on both of them: conceptualization, the minimum part of production.

But in the end they chose They Always Run. And today we are all very happy about it. The name, by the way, was invented by the Lead Developer of the game Vadim Ukolov.

The strength of They Always Run is the visual style. The whole game is drawn manually. Moreover, almost a classical technique is used (visually resembles the alla prima oil approach), unusual for CG. Tell me how they came to her.

Stepan: Many players complain that the games look the same today. We also see this. Therefore, when working on the visual style, we immediately set ourselves the task of making the game look graphically original, unlike anything else.

Our team of 2D artists is cool. On the one hand, everyone has a lot of experience working with familiar CG, and on the other — everyone has a classical art education.

Such academism against the background of creative searches led us to the chosen style. We realized that we wanted to try something picturesque, with three-dimensional strokes. And as a result, our artists came off on this project.

What other visual approaches have you considered?

Stepan: We thought about the possibility of creating a game using pixel art. But a game made in this style would no longer look as original as we wanted.

Also, at the very start of prototyping, we were thinking about whether to make the characters in 3D. We refused it for two reasons:

- we have a linear platformer, not a role-playing game and not a metroidvania, where there are a huge number of weapons. Therefore, it made no sense for us to implement 3D to speed up production, while losing our visual identity.;

- the chosen aesthetics was more important to us than the flexibility of the approach (we tried to integrate 3D, we didn’t like it, we realized that this is not the graphics we want in our project).

They Always Run

Before we go deep into the discussion of visual technique and production, I would like to go back a bit. You said that They Always Run is partly inspired by the TV series “Firefly” and “Cowboy Bebop”. Did such a source of inspiration greatly influence the choice of colors and palette, which also seems pastel in places?

Stepan: I really love “Firefly”, I watched it in its entirety several times and periodically review my favorite episodes. From my point of view, he is absolutely brilliant in his simplicity.

In They Always Run, our goal was to capture the feeling of a space adventure with a team on a ship, where different characters are forced to unite for a common goal and travel together. But this is not a literal story about cowboys.

They Always Run is a space western, but also an action game about a bounty hunter. And the second source of inspiration was just the TV series “Cowboy Bebop”. It also has a lot of western in it, but it’s still an action game, and we wanted to capture its spirit and do something of our own. We have a race of three-armed mutants, to which the main character belongs, a cool and interesting ent has been invented, which helps the story develop.

I don’t think it affected the palette. And if there are any intersections, they are unintentional. Of course, we had refs for inspiration, but we are not interested in copying, because we ourselves have a fountain of different ideas. I hope that we took a pinch of the other, added our own and got something at least to some extent unique.

I was also hooked in the picture that you managed to convey the spirit of 80’s fiction in places. Was it a conscious intention and if so, how was it achieved?

Stepan: It’s unintentional.

I think potentially it turned out like this: we all read fiction and played many games. I’ve played ZX Spectrum, Dendy, Sega, Sega Dreamcast, PlayStation, everything possible. Some of my favorite games are Flashback and Another World. They are very different. We definitely didn’t consciously copy screenshots, level fragments, or a palette from these games. But, nevertheless, I find comments on various resources that They Always Run is similar to Flashback. Or on Another World. And I think how? After all, I didn’t even draw these backgrounds!

So I can reliably say that it did not happen consciously, but automatically. Apparently, it became part of some internal genetic code. And I somehow moved artists towards what I like inside.

So, back to the drawing technique. Its uniqueness, it seems to me, first of all catches the eye when you look at the backgrounds. Can you share a blueprint for working with backgrounds and level elements?

Stepan: Yes, of course.

It all starts with the concept.

The designer sets a task: for example, you need a level with a space base. At the same time, as a rule, the level itself is already ready.

Starting from the task, the artists draw a fake screenshot. This is necessary so that we can decide how the level will look, what color scheme we will choose, what elements we will use.

When a concept appears in color, then we make a set of fragments based on it, which we impose on the level design.

The location itself is built from small pieces, some unique, others are repeated. Artists take and arrange them, finish the necessary pieces somewhere. For example, there is not enough gas tank for the background and there is not one in the concept — we take it and finish drawing.

Gradually, everything is laid out like a mosaic.

I think this is done in many games. We looked at how it was done in the same Ori — there is a foreground, depth, background. All this fits into a kind of pseudo-perspective. And we also made everything up in pieces. The process is quite lengthy, handmade.

They Always Run

Now you’re talking about pieces. Is it possible to say that the level is built from tiles?

Stepan: If we take the word tile as a repeating fragment, then in our database we use tiles that do not go joint to joint, but overlap on top of each other.

For example, we have a stone wall with soft edges and 7 types of how it looks. This softness is made up of tiles so that the repeatability is not too visible.

It is clear that we could not physically draw every centimeter from scratch, so there is repeatability, as in any other game. But we tried to make the tiles different so that there was a sense of uniqueness, as much as possible within the level.

You mentioned just above that the process is quite time-consuming. How much time does it take for one level to use such a technique?

Stepan: Let’s say there is a level consisting of cubes, which was made by a game designer, and there is a concept. We take this concept and wrap the level design with graphics – this process can take three weeks or a month if the level is large.

Everything is drawn on the go. I look, I look at the points of the process, but the artist himself makes decisions about the objects that will be there. That is, a lot of work lies on the artists, because they draw in real time, and report it to the game, and finish drawing where what is missing. And in fact, the visual work on the game was done by the artists themselves in terms of backgrounds. They are both artists and “visual level designers”.

With animation, you didn’t look for easy ways either. You have it all drawn frame by frame. Why did you decide to take such a step?

Stepan: I’m a fan of frame-by-frame animation, I love such cartoons, especially the old ones, like “Roads to El Dorado”. I also like 3D cartoons, but it is frame-by-frame (not a shift) and it is 2D that is much closer to me in aesthetic feelings.

Of course, it is easier to visually change the character with a shift if he has upgraded. In frame—by-frame animation, you will have to draw everything – the process is complex, time-consuming and time-consuming: you sit for hours drawing frames to get a second of animation.

Did you regret it (it would definitely be easier with Spine or 3D)?

Stepan: No, they didn’t regret it. Each of the paths has its pros and cons. 3D is good because many things are done automatically. Let’s say the same lighting maps are conditionally rendered simply by a button.

But we have aesthetics at the forefront. I drew the absolute majority of sketches and many animations in color, and it was important to me that the character moved the way I needed. It is difficult to achieve this in 3D, there is a completely different vibe.

Probably, my love for 2D, baked into DNA, plus a team of artists focused on 2D, played a role here – everything worked out. And we were not disappointed, we did everything in 2D with manual painstaking work, and visually it turned out great.

They Always Run

But how much more time does such animation take compared to other approaches?

Stepan: I’d say it’s crazy. And, most likely, no one will do this, because it is very labor-intensive. If you compare it with Spine animation or 3D, then everything is done much faster there.

It’s hard for me to tell by the number of hours or days, but I think frame-by-frame animation is not 2 or even 3 times longer and more labor-intensive. It seems that you need some kind of broken cluster in your head to sit for days and draw so much for the sake of one second of animation.

In addition to the time spent working with it, what are the other disadvantages of frame-by-frame animation?

Stepan: Not everyone will be able to do it. Here you need perseverance, an artist with a special warehouse, one who likes to work on frame-by-frame animation.

Another disadvantage: the flexibility of such animation is zero. If the spin animation somehow doesn’t look like that, it can be relatively easily corrected. The same thing in 3D: I moved the bones, changed the animation.

And with frame-by-frame?

Stepan: Here, if something went wrong, you need to go redraw everything from scratch. Each “shot” must be accurate.

I don’t belittle the merits of 3D or spin animation. They are also difficult and painstaking to do, especially if done well. Perseverance is required in any case, if you are an animator.

And we cannot say that some approach is better, which one is worse. It’s more a matter of choosing a technique for a specific project.

I also admired the work with lighting animated objects. It is especially clearly visible in the trailer for E3. Tell us a little about how you worked on the lighting in the game?

Stepan: We used the most difficult way possible.

The light from the light sources was supposed to influence the characters — this was one of the goals of the aesthetic picture. In some games I have seen such semi-automatic things, when a pixel contour along the edge of a character simulates lighting on the border of a sprite. And I wanted the light to illuminate the very shape of the character, enveloping it depending on how he moves.

In 3D, this is done automatically: you just set the model, set the parameters for the light, and it both illuminates and casts a shadow. In 2D, the game has no data on what shape a flat sprite has. This data needs to be communicated to the game, so we drew lighting maps for each frame. The animation work increased 5 times, because each frame needed 4 different states of light. They were baked into a kind of map, which told the game the shape of the object and information about the depths of what is imprinted on the sprite.

So for 1000 frames of animation, we have another 4000 frames of light drawn by hand. But we got exactly the effect we wanted: the light works according to the shape of the character, as if it flows.

They Always Run

We have just discussed the difficulties caused by the chosen drawing technique. And would there be any non-obvious problems (like those that Blasphemous had, where the chosen perspective turned the platforming into hell)?

Stepan: I would say that the non-obvious difficulties turned out to be 10 times more than I expected, and not only in the schedule.

When I became a producer and looked under the hood of the game (although I always tried to delve into all areas), I saw how many decisions I had to make during development. And I began to appreciate much more what I see in other games.

Even in games with a side view, where the character exclusively runs and jumps, there are many invisible schemes that allow the player to feel comfortable with her.

It may seem that you are running from left to right, pressing jump, jumping. What’s complicated about that? And there are many nuances. With what force does the character jump? How far does it fly? Does he somehow change his position at the peak of the jump? When he flies from top to bottom, does he look different somehow? Does it have a landing animation? When a character in the landing animation, can it move if the player presses move? How long does each of the micro-slices last?

And since we have a lot of animations (only the main character has more than 300 of them), all the transitions between them are woven into a mind-blowing pattern that should work and give the right feeling. I’m talking about the visual part, but there is also a software part that puffs under all this. There are a lot of designs under the hood, and the player’s feeling depends on the foresight of how we designed everything.

I’m sure everyone involved in games understands what I’m talking about. And those who are engaged in giant AAA projects with open worlds – they are probably geniuses in general.

Thanks for the interview!