In August, the producer of Halo 3 and Halo: Reach, Matthew S. Burns, released the indie game Eliza. The psychological drama about the human right to choose has garnered high marks. However, it went unnoticed by the general public. We talked to Matthew about the development of the game.

A little about the project

Eliza was Burns’ first personal project. This is a narrative quest about the near future, where AI replaces psychotherapists. The project is published by Zachtronics, a company specializing in hardcore puzzles.

Interview

The editors thank you GOG.com for help in organizing the interview.

Oleg Nesterenko, author App2Top.ru : Matthew, before you joined Zachtronics, you worked at Treyarch, Bungie and 343 Industries. What were you responsible for in these companies?

Matthew S. Burns (Matthew Seiji Burns)

Burns: I was a producer in these studios. I was responsible for production plans, for ensuring that all game assets were prepared in order and on time. I was monitoring whether we had enough personnel. All in that spirit. My area of responsibility included three areas of development — design, animation and audio.

You also checked into the video game research lab at the University of Washington. What were you doing there?

Burns: The lab I worked in was called the Game Science Center. There my role was quite akin to a producer’s. I was busy with the daily management of the research group. The work was very interesting. I remember with warmth the time I spent there. For example, we found out how to combine different approaches to solving complex tasks, such as protein folding, most effectively.

But in the end, you still left science back to game dev. Why did you choose Zachtronics? Judging by Eliza, you wanted to do story projects. Zachtronics, which produces games about coding, is not the most obvious candidate here.

Burns: Indeed, Zachtronics is far from the studio that you think about when it comes to games with a plot. But that’s partly what attracted me. I’m not interested in “telling stories” for their own sake. I believe that stories must be connected with something in order to come to life, to become real.

All of Zach’s games [Zach Barth is the founder and creative director of Zachtronics. – Ed.] carefully thought out from the point of view of history, even if it happens in a fictional world. Let it not be noticeable at first glance, but Zach takes the plot very seriously and has been engaged in it since the first days of the development of every game — even those devoted to programming in assembly language.

Zack is always wondering why players are ready to perform certain actions even before he asks them to do it. The gameplay of all Zachtronics games is usually reduced to operating with abstract symbols. And it always makes some sense.

And now Eliza appears in the line of abstract puzzles. What kind of place does she have in her studio portfolio?

Burns: Eliza is a unique experiment for the studio. However, those who are familiar with the plots of other Zachtronics games will see a lot more familiar features in Eliza than they could have expected at first.

All studio games: Infinifactory, Opus Magnum and EXAPUNKS, and even SpaceChem, which was released back in 2011, study the causes and consequences of actions performed by players. In this context, we can say that Eliza is developing the studio paradigm, and not moving away from it.

Great! But at the same time there is a feeling that Eliza is a painfully personal game. One of its main themes is burnout at work. You also wrote a book about it — “Survival in the gaming Industry”. What kind of negative experience did you have when developing AAA games?

Burns: Look, this experience is definitely not bad. However, I did encounter unpleasant things. My health, both physically and psychologically, was severely shaken due to the culture of crunches and stress in the places where I worked. One of the studios where I worked a few years ago recently appeared in the news: it was just accused of creating poor working conditions.

Looking back, I think maybe I should have resisted it more. But I was young and wanted to look like a good employee, so I let it happen.

Most of Eliza’s story and gameplay revolves around psychotherapeutic consultations. Are you relying on your own experience here? Is it okay that I’m asking about this?

BURNS: It’s all right. It would be strange if I didn’t have this experience, wouldn’t it?

My personal experience of visiting a therapist greatly influenced the game.

First, I took the general structure of sessions from them. The therapist starts by chatting about the weather, and then gradually moves on to more and more significant topics.

Secondly, I realized that it is very difficult to start talking about yourself. And when you talk, things go easier, because the interlocutor asks leading questions. This was also included in the game.

I think it’s important to say that my personal experience of therapy has been generally positive.

Before developing the game, you did your own research. Within its framework, you took several interviews. One of them was with a therapist. How did you approach such people in general?

Burns: I was interested to learn more about the methods, how psychotherapists are trained, what they think about their work. I was lucky. I found those who were willing to talk about their work, who were honest and talked about the limitations in their profession.

What did you find out during these interviews that you then inserted into the game?

Burns: I realized two things, which I then reflected in Elize.

First. Practitioners are very fond of numbers. For example, you may be asked: “How do you feel on a scale from 1 to 10”. And you may be asked about it at every meeting or regularly throughout the day.

Measuring mood in numbers is, if you think about it, a strange approach. So I decided to discuss it in the game.

Second. I was looking through a textbook for practicing Cognitive Behavioral Psychotherapy (CPP) specialists and realized that many actions, including those of real therapists, are conditionally scripted.

Cool! It turns out that one of the central conflicts of the game was just the result of your research work. And isn’t it connected with this that the real possibility of choice for the hero of the game appears only at the very end of the game?

BURNS: Not really.

Imagine the situation. The game has just begun. Your character immediately has a choice, say, to go outside or stay at home. This choice will not make sense and, most likely, will be largely accidental or will depend on what you yourself want to do now in real life.

Linearity over a long period of time allows me to create more complex situations. Maybe your character doesn’t like to go for a walk, but today you still need to go for a walk, because the hero had a fight with his father at home. Suddenly, this choice became more interesting when the context appears — more heroes, more history.

So I’d rather spend a lot of time building one complex, interesting choice than give the player the opportunity to make thousands of small decisions that, by and large, will not affect anything. However, some games go this way.

Before Eliza, you spent some time writing interactive novels on the Twine platform. And initially, the game was also supposed to be one of these stories. How difficult was it to switch from creating short stories to a full-fledged game?

Burns: Thanks to working with the artists and actors who voiced the game, the development turned out to be more… let’s say, a collective process than before.

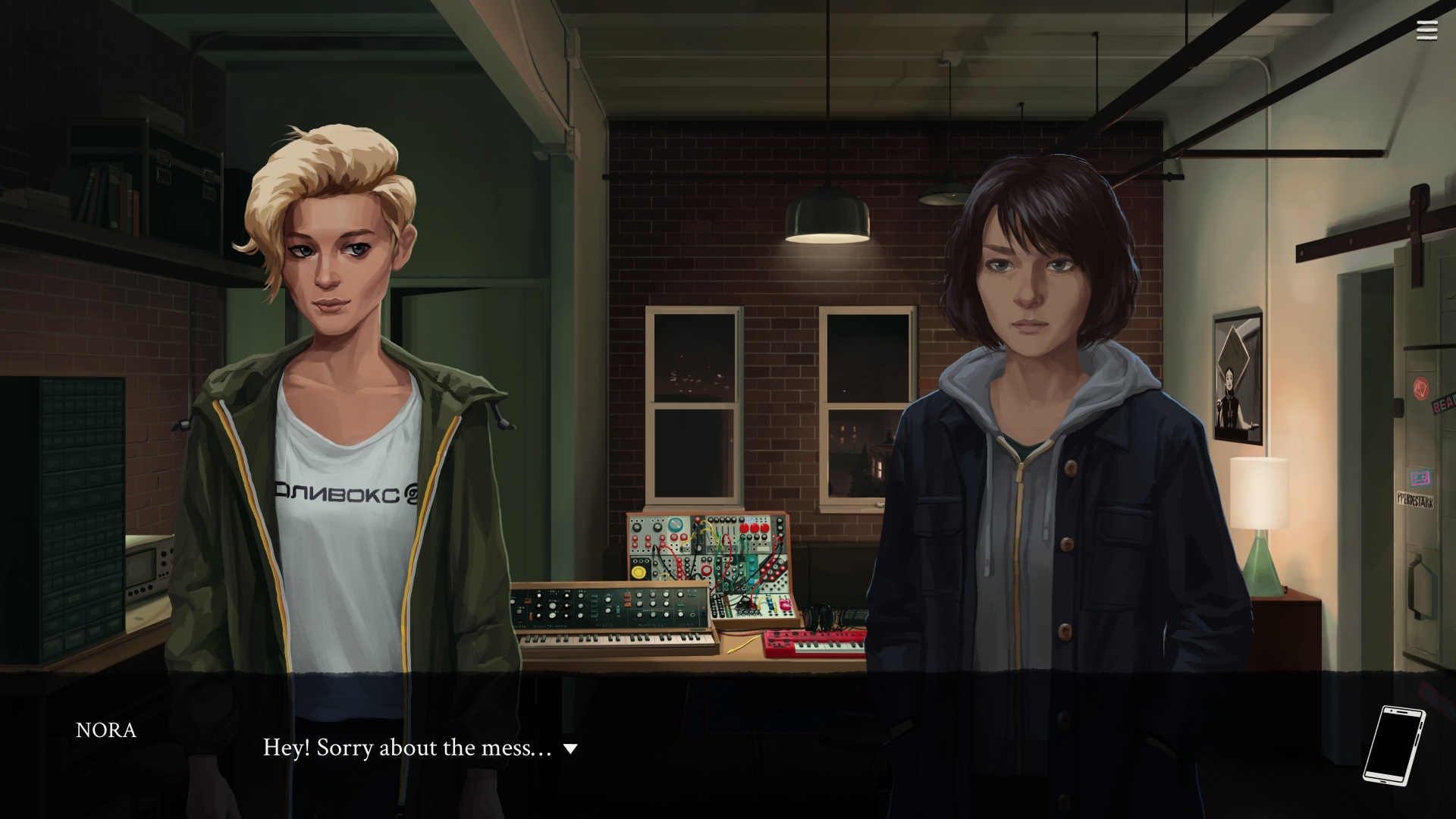

There was very little visual content in my Twine games. Eliza is a completely different matter. Therefore, we have to solve new tasks in the spirit of: what should the characters look like, what clothes do they wear, what does it say about them?

When creating a text game, the visual image of the hero may be vague. Sometimes a small remark is enough. However, when the characters are fully drawn, each choice of one or another external feature determines the character. And artists regularly contribute their vision to clothes, poses, facial expressions.

The same goes for actors. It’s one thing to write a text that no one will say out loud. The text that the actors voice is quite another matter. I had to adapt one type to another. A lot of information about the character is transmitted by the actors’ game, and then it is no longer necessary to put this information into the text itself.

Is there a fundamental difference between writing games and working on stories?

Burns: Not really. I will even go further and say that for me there is no fundamental difference between writing lyrics and writing music. There are many technical differences, a different language, but in fact we are talking about the same process.

And this also applies to games?

BURNS: Yes. For me, games are no longer separate entities, just as architecture is not a series of buildings, and philosophy is not a stack of books. The buildings around are the result of an architectural process; a stack of books is a philosophical one. It’s the same story with games. For me, they are a set of technologies, tools, techniques that we use for development. They are language, grammar. In general, everything that we use for entertainment, learning and the realization of true creative expression.

Matthew, thanks for the interview!