Part [1/2] – Free-2-play principleThe principle is to give the player the opportunity and incentive to spend as much money as he is willing to spend.

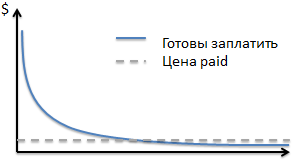

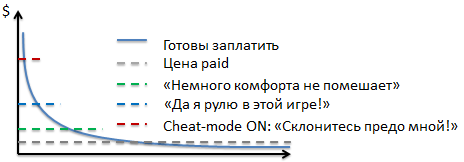

Below is a graph of how much the user is willing to spend (vertical Y axis) and the number of such users (horizontal X axis).

The graph shows that only a few are ready to spend a lot ($1000+), and the vast majority are ready to pay quite a bit (~$5 or less). This means that, ideally, the income will be equal to the area under the blue line (each user pays the maximum amount possible for him).

In the case of a paid model, you cannot offer everyone a suitable price for him, you are forced to choose a specific price tag (for example, $4.99). In this case, your income is only that part of the “ideal income” that is under the dotted line.

Offer (lay) several options!How to get an “ideal income”?

Give players the opportunity and incentive to spend as much as they can. That’s what free-2-play is all about, not making the game free by adding in-game purchases instead.

Game content should initially be designed for several categories of players according to the amount of total spending. Moreover, the gradations differ rather by orders of magnitude, like “$1-$10-$100-$1000”.

It is impossible to provide the same difference (by 3-4 orders of magnitude) in the quality of in-game content, and it is not necessary. It’s just like in life – the price increases geometrically, and if the quality of the product increases, then not so much. And often the overpayment is purely for the brand-image component.

Part [2/2] – Examples and techniquesExample 1: Content gradation

a) In the browser projects I have worked on, content gradation has always been applied:

- Gray [80%] – $1: basic content available to everyone without any effort, you just have to want;

- Green [100%] – $10: Content that is a feasible game task to obtain;

- Blue [150%] – $100: Content owned by either paying or hardcore players;

- Purple [190%] – $1000+: content available only to owners of an unlimited wallet or truly unique players (2-3 per server).

This principle was used everywhere when introducing content: character equipment, the power of mounts, pets, the power of buffs, the power of sharpening weapons, the difficulty / effectiveness of leveling reputations.

As you can see, the increase in conditional capacity compared to the price is insignificant*.

* – ATTENTION, the given values of capacity and price growth are AN EXAMPLE. Things like this depend a lot on the project.

b) You can buy two types of shells in WoT: 23 damage for 3 software

- 46 damage for 400 soft (or for 1 hard)

Not everywhere and not always it is possible to clearly divide the content by conditional capacity. For example, it’s harder to apply in a farm than in an RPG. The following examples will help in this case.

Example 2: Price progression a) There are no clothes or unit strength in Hay Day.

But there you can buy an additional slot in the production queue. The advantage is small, but you can enter less often. Opening each subsequent slot costs more and more money. At the same time, if the cheapest opening of the second slot doubles the number of your slots, then the purchase of the 11th slot, which you don’t really need, will cost very, very expensive.

b) In WoW, the purchase of additional slots for bags in a bank cell is growing exponentially. And again – the first few bags, which are enough for many, can be purchased by almost any player (in fairness, the earnings of the game currency are also growing significantly in WoW).

I don’t think that such a technique makes the main income in the market, but it should be in the arsenal of a game designer.

Example 3: Apply the f2p principle everywhere

Promotion – if during the action the user contributes X or more dollars to the game, then as a bonus he is given a lottery ticket. It’s a small thing, but it will stimulate you to deposit this amount, even if it is slightly larger than the usual payment size for you.

The trick is to choose a payment size that would maximize profit. If you demand too little, you will not notice a strong difference in income, but everyone will get a ticket. If you demand too much, out of all those paying, only a couple dozen will be able to overpower this amount.

The situation is a direct analogy in choosing the price for the application (see the graph above).

If we apply the principle of f2p and offer several options, then the solution is the gradation of payments:

- Payment of $30 and above – guarantees the receipt of a lottery ticket;

- Payment of $50 and above – in addition, the player received a good combat potion (price $1-$2);

- Payment of $100 and above – among other things, the player received 1 out of 5 unique gifts (just a decorative picture that could be given to someone);

- And for the most persistent – a repeated payment of $ 100 and above gave another 1 out of 5 gifts (here as a random will fall). Such a decision increased the income from the stock several times.

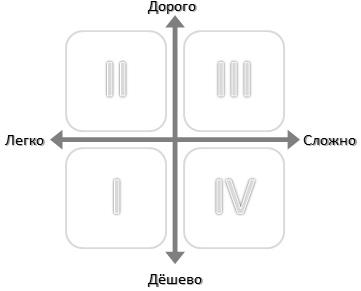

Example 4: Course matrix In-game resources-goods can be evaluated according to two criteria:

the difficulty of getting in the game and the cost of acquiring for hard. Let’s build a matrix based on these criteria:

- Quadrants I and III “Easy – cheap“ and ”Difficult – expensive”

Fairly valued resources are goods, there is nothing much to consider here;

- Quadrant II “Easy – expensive”:

Such an assessment can serve as a tax on “paying” – a way to receive payments without creating difficulties for ordinary players. Time-skips and energy can serve as an example – it’s almost worth no effort to wait for a few hours, but skipping waiting is already for money.

- Quadrant III “Difficult – cheap”:

Such an assessment course can be a good incentive to pay, and accordingly contributes to an increase in conversion to paying. An example might be a starter pack, a bundle for a beginner.

Other materials on the topic:Pixonic Seminars: about choosing a concept