Mark Brown, an indie developer and editor of the Pocket Gamer resource, spoke about the important role of restrictions in game design within the Game Maker’s Toolkit video cycle. With the author’s permission, we have prepared a printed version of the material. We share.

There’s a moment in Uncharted 3 when Nathan Drake is about to jump from one ship to another and says, “Okay, here’s the ladder. I only have one try.” And it may seem that you really have only one attempt.

But if you screw up and die, it’s a game. You will be reborn in the same place, and in just ten seconds Drake will say again that he has only one attempt.

Games sometimes don’t let you raise the stakes, right?

Perhaps that’s why there are so few good projects about robbery. Especially if we are talking about a singleplayer. Why do you need a game about a large-scale robbery, in which, if you happen to catch the eye of a security guard or be killed, you just start with the last checkpoint?

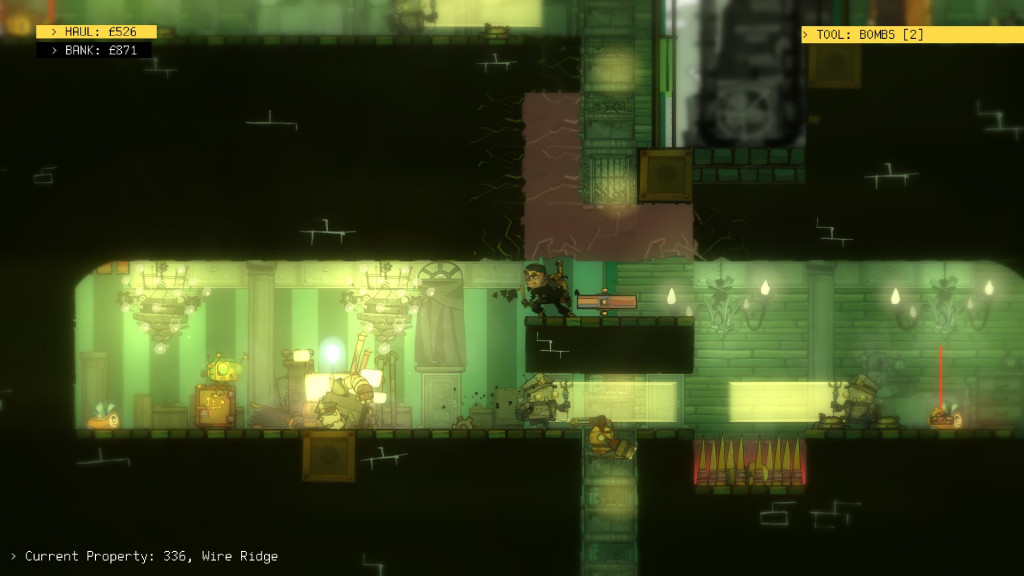

And now let me introduce: The Swindle.

That’s where you feel the real pressure. You know, if you screw it up, you’re going to be thrown back a lot, so the stakes are pretty high.

But it’s not just tension that creates the atmosphere here. It is also necessary for the robber to feel the thirst for profit – to take risks and take more than necessary. Because that’s how the best stories come out. The Swindle also successfully copes with this task.

So, let’s figure out exactly how the game manages to make a virtuoso robber out of a player.

The Swindle is a platformer with elements of stealth mechanics. The player needs to attack enemies from behind, deactivate mines, sneak unnoticed past surveillance cameras and hack terminals. In each randomly generated level, you need to collect as much money as possible before you decide to leave it. The money that was stolen is spent on the purchase of various abilities – the ability to make triple jumps, create bombs, move more quietly or see further. Plus, access to the next levels also costs money. This also applies to the final level called The Swindle (this level is called the same as the game – approx. editorial offices).

There are two secret ingredients in the game – because of them, you ignore small stashes of money and try to get a bigger amount.

To begin with, you have a time limit of 100 days. Any robbery, whether successful or not, takes one day. If you don’t complete the final mission before the 100-day deadline, the game ends.

Plus, there are bonuses in the game. If you collect all the money in the building and no one notices you, you get a “bonus for invisibility” (ghost bonus). If you collect most of the money at the level, the reward will be experience points. You will be able to stay alive for a long time, and for each successful sortie you will receive large bonuses.

Because of these two systems, you constantly feel pressure. Mess up and lock up the level – which is quite easy to do, because they kill you with one hit – and you won’t get anything. Yes, and you will have to play for a new character, which means that you will be pumped from scratch.

In addition, these two systems force you to steal as much money as possible and take big risks. I want to get a bonus for invisibility and experience points every time.

Which is very correct: after all, playing this game is most interesting when you get into dangerous situations.

If you take a big risk, then there are three options for the development of events. The first is that you will do the impossible and run away with a lot of money, like a kind of ninja thief. This is a very good option. The second is that the alarm will turn on, but while sirens are howling in the background, you will still hide with the money. This is also a good option. Third – you will completely fail the passage and lose the loot. It’s not great anymore, but in the long run, maybe not so bad.

Every defeat brings you closer to the end of the 100-day period. The tension is growing, you are more and more greedy – and you are taking risks more and more often. As a result, you either start losing more often, or one day you win and commit an epic robbery.

Here it should be noted that the game punishes for losses, but not too cruelly.

There are other projects where everything revolves around preparing for the final mission – for example, FTL space survival or cyberpunk spy thriller Invisible Inc. But in them, if you screw up, you either fly out of the game, or you find yourself in a very disadvantageous position.

The Swindle is a little more forgiving of the player. The final mission can even be replayed, although it will have to quickly collect £ 400 thousand. Which – yes, you guessed right – makes you take risks more often.

In fact, The Swindle is a great example of how developers use game design to achieve certain behavior from a player. Without the 100-day limit and other systems, the game would be perceived quite differently.

And I know for sure that this is exactly the case. I talked to The Swindle’s game designer, Dan Marshall. He said that at a certain stage of development there was no 100-day limit. But an early build of the game was shown to one journalist, and he quickly realized that it was much safer to steal some money, get out of the level, and then repeat the same thing a couple hundred times than to risk big and try to steal more right away.

The journalist, by the way, should not be blamed. This well-known phenomenon in game design is called “dominant strategy”. If a player finds a loophole in the system with which he can win without any problems, he is likely to use it. And it will be used again and again, no matter how boring or dull this method is.

So do not hope that the players themselves will choose the most interesting way to play the game – for example, they will risk everything for the sake of winning, as in the case of The Swindle. Without the appropriate motivation or reward, the user may never see the game as you intended it to be.

The game designer should place the accents in such a way and configure the systems so that the players behave as intended. In The Swindle, it is due to the efforts of game designers that the feeling is achieved that you did not steal a chocolate bar from the buffet, but committed a robbery of the century.

Source: Game Maker’s Toolkit