What is interesting about Her Story from the point of view of game design, – Mark Brown, an indie developer and editor of the Pocket Gamer resource, told as part of the Game Maker’s Toolkit video cycle. With the author’s permission, we have prepared a text version of the material in Russian. We share.

Her Story is a very unusual detective game and the best thing I played in 2015. In it, you get acquainted with the plot at your own pace and on your own terms.

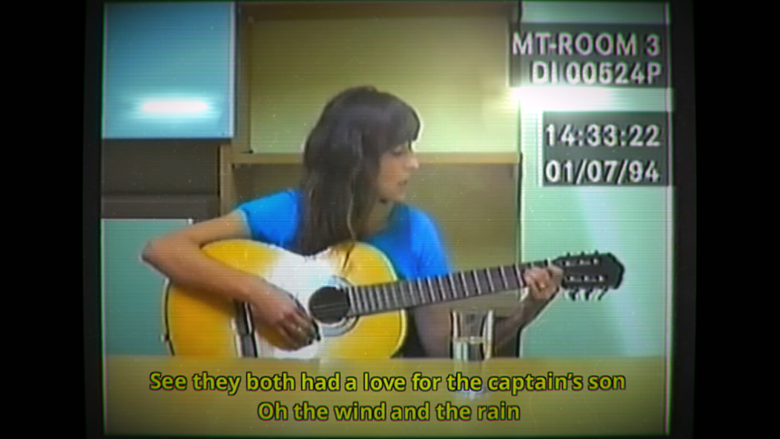

This game — in case you haven’t played it — invites the user to dig into old videotapes. They record how Hannah Smith, the main character of the game, tells the police about her murdered husband Simon.

But the seven interview tapes can’t just be viewed in chronological order: each was broken into pieces and poured into an old-fashioned database called LOGIC. To find the right film, you need to type a query in the search engine window. And if a word or phrase occurs in one of the records, then this record will be in the output.

It may not sound particularly impressive. It looks like a Google manual. But, believe me, the process drags on.

You watch the recording, and there Hannah says something like: “I must have been knocked out. I was in Glasgow at the time.” And you’re like, yeah, Glasgow! You enter the name of the city in the search and watch new videos. You start looking for names, places, recurring motives, cause-and-effect relationships in Hanna’s stories. You write something down, draw a timeline, make notes about inconsistencies. You check different leads — some are put on the wrong track, and some give useful information.

Her Story

Slowly but surely you are making your way through all the intricacies of the plot and a picture of exactly what happened looms before you. And why.

It turns out to be a very personal story, because only your own curiosity and intuition leads you all the way. Only you decide in what order all the fragments of the plot will come together.

Or not?

Maybe, in fact, the game is very carefully pushing you in the right direction to the right videos? And by the way, what prevents a player from accidentally stumbling upon the most recent video and watching the end of the game even before he really started playing, and immediately realize that Simon…

Okay, stop. To dive deeper into the mechanics of this brilliant game, I need complete freedom. So if you haven’t gone through Her Story yet, it’s better to close the text tab right now, go to the App Store or Steam and buy the game.

Legacy of Kain: Dead Sun

Well, now let’s continue.

When the Legacy of Kain: Dead Sun game was never released after three years of development, Sam Barlow quit console games and quit Climax Studios. At the same time, he decided that his first independent project would be about interrogations: he was fascinated by the way they are shown in documentary series. In an interview with the Develop Online resource, Barlow said that he sees the interrogation room as a kind of gladiatorial arena, where a duel between a detective and a criminal takes place. The interviewer must understand the train of thought of the suspect, “split” him, trick him into giving himself away.

Some developers are trying to reproduce this atmosphere. But so far no one has really succeeded. The player either goes one step ahead of the detective, as in the game about the Ace Attorney’s judicial investigation. Or he doesn’t have the opportunity to ask the questions he wants to ask — as, for example, in LA Noire. In this game, Detective Cole Phelps has only a strictly defined set of questions, and the suspects have only three possible answers. This approach makes it very difficult to conduct a dialogue and does not allow you to fully feel the excitement of catching the killer.

It is clear that it is impossible to give the player a chance and do whatever he wants. Barlow faced this problem back in 1999 in the debut Aisle game. In it, the player could do whatever his heart desires — eat pizza, chat with a woman, strip naked, dance, smile, scream or sing. What’s the catch? The player could perform exactly one action, after which the game ended.

Creating dialogues in games is a difficult task. Barlow spent long hours watching real interrogations and in the process realized that the game would not be about how to ask questions, but about how to listen to answers. In addition to detectives, Barlow was inspired by another type of interviewer — psychiatrists. One such character played a significant role in another famous Barlow game — Silent Hill: Shattered Memories.

Silent Hill: Shattered Memories

The main idea of the game — to mix the video and let the player figure out the plot himself — Barlow learned from J. G. Ballard’s experimental novel “The Exhibition of Cruelty” with a non-linear narrative.

The problem was the following: how to make the player understand where to move, not get lost and not accidentally stumble upon the end of the game.

When Barlow first started working on the project, he was going to make the structure of the game more traditional. It looks like a mosaic. The player did not get access to certain parts of the interrogation until he watched certain videos or typed a very specific keyword.

But then Barlow tested the database for Her Story with the help of a real interrogation from the case of Christopher Porco, a student from New York who hacked his father and almost killed his mother.

Almost everything Porco said—even the answers to very simple and unambiguous questions about hobbies and biographies—boiled down to a conversation about money. As soon as Barlow started searching for words related in meaning to the word “money”, he was able to move back and forth through the record and find more and more important details for the case.

Her Story

When Barlow found out in this way that Porco had killed his parents in order to get an insurance payout, it became clear to him that the player should be able to freely navigate through the archive of testimony, and not open closed videos in turn. Moreover, it should be led by hints scattered across the answers.

This is the way Barlow chose. Enter any word in the search bar, and you will have access to each of the 271 videos where this word occurs (with the nuances described below – approx. editorial offices).

But this does not mean that you just need to type everything that comes to mind. Barlow hints quite transparently how to move between cuts — at least at the very beginning.

It all starts with a word that has already been typed into the search bar: “murder”. In one of the videos, Hannah talks about it like this: “How does this relate to the murder of Simon?” Type “Simon” in the search bar, and this will lead you to a video where Hannah mentions the name of the area — “Rock”. You type the word “rock” — you get a segment in which the heroine mentions a certain Eric. You type the name into the search bar, and Hannah says: “Have you seen his wife, Diana?” The name Diana will lead us to a video where Hannah says that “she was in Glasgow then.” Glasgow refers us to a video where she says she “told him about the pregnancy.” And that leads us to… well, you get it.

All this time we have other videos, other puzzle pieces and other words to look for. So there is no feeling that we are being led along a certain path.

Her Story

But in just a couple of cuts, everything falls into place, and we already have an approximate understanding of the plot.

Of course, you can type any random word into the search bar. Or rely on intuition and see where it leads.

But then it turns out that Barlow anticipates your every move.

You check a random guess about a knife as a murder weapon — get a useless clip in which Hannah tells how a random character snatched off a lock of hair with a bread knife. Nothing interesting.

But try to ask a question about Hannah’s bruise or about Eva’s tattoo (Hannah’s twin sister, – approx. editors), who hide from the view, then behind a guitar, then behind a glass, and you will get a bunch of videos. The game just doesn’t wink at you and say, “That’s right. Now you’re on the right track.”

Her Story

Immediately you feel very smart. You’re just like the cop who picked up the trail.

Or, for example, you ask about a tattoo and get the answer: “There’s an apple and a snake. Simon guessed my name from it.” You’re like, maybe her name is Eva? You type that name… bam! Five new clips.

Stunningly.

Sometimes Barlow puts you on the wrong track. He knows where you’re going next and uses that knowledge against you. At some point you catch yourself thinking — wait a minute, does Hannah have a twin sister? But if you start looking for a clip by keyword, you’ll find a video where Hannah says, “Twins? Seriously? Are you seriously asking me about this now?”

So what is it that prevents the player from stumbling upon a clip where Hannah or Eva reveal key details?

After all, you can take and from the very beginning accidentally find a video where Eva describes the murder in detail: “She grabbed a shard, waved it and cut his throat.” To do this, you need to type the words “clothes”, “real”, “crazy” or even just the name of the game. Or you can stumble upon another video where Eva says: “We cleaned up, stuffed the broken mirror into packages. And her clothes. Everything was thrown out. The body was taken to the basement.” This video will appear if you type “ceiling”, “alibi” or “clock”.

Her Story

Here’s the thing: the chances that you will accidentally stumble upon the substantive part of the interrogation are not so great, because if you look for more appropriate words like “mirror” or “body”, then you will not find these videos. All because of a tricky restriction placed on the search results: only the first five results are visible, and the segments themselves are arranged in chronological order. All the most meaningful excerpts are at the very end of the list of 271 videos.

This means that important videos are likely to be hidden behind a cut from an earlier part of the interrogation, where the same words are used in a completely different context.

So Barlow never breaks his own rule. All videos are available throughout the game. But he can manipulate the results, so that the player looks at the excerpts in the correct order.

And don’t forget that the segments where Eva describes the murder don’t mean anything without context. The heroine simply says “she”, “her”, without naming a name. So even a tape with a murder story is not the key to all the doors. Each video is specially composed so that nothing is clear without context.

The intricacies of the plot also make it difficult to figure out what’s what: two women meet with the same man at different times. So even if you watch a bunch of videos, you’ll only find out who the killer is. Not a motive.

Her Story

No one will be handcuffed at the end of the game. And the player will not be forced to choose a killer from the options offered. The goal is to understand why the crime occurred. Or at least get closer to understanding, because the game allows for different interpretations of events. You can trace the sequence of events step by step. But is it possible to trust the person who told about them? Don’t the narrator’s intonations and hints of hidden meaning make you doubt what she is saying?

So yes, Sam Barlow does allow the player to explore the game freely. And if you’ve read my other texts and know how much I don’t like when a player is led by the handle, then you’ll understand why this is so important to me.

The example of Her Story proves that the ability to give the player freedom is an art. This does not mean that you should stupidly let him do what he wants — and hope that a good game will turn out by itself. This means that you need to gently push him in the right direction and not let yourself spoil the whole fan. But without him noticing anything. And I didn’t realize that the game designer was standing behind the stage and steering the process with a confident hand.

Source: Game Maker’s Toolkit

Translated by Irina Smirnova