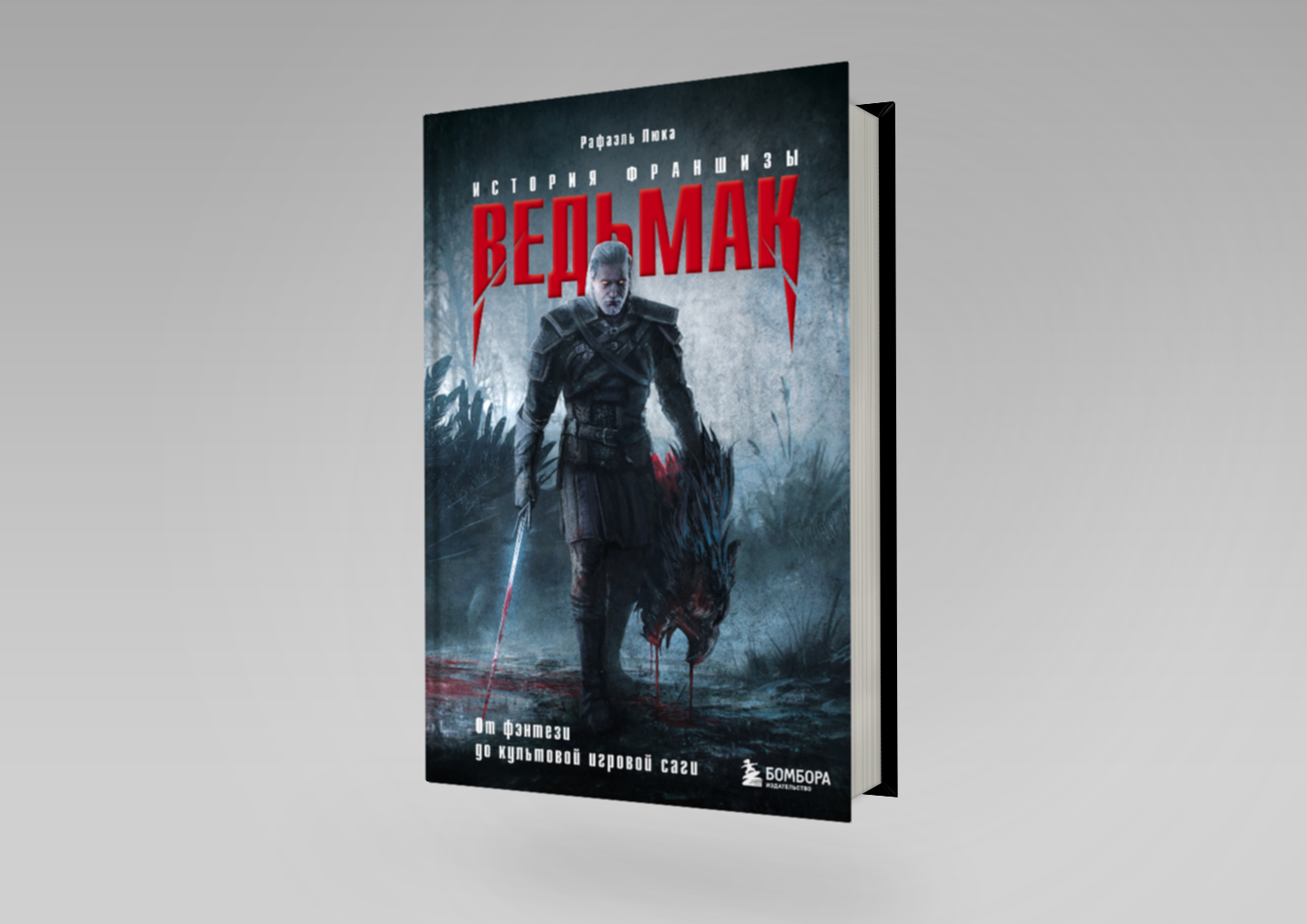

The Bombora publishing house announced that the book “The Witcher. The history of the franchise. From fantasy to cult game saga” by the authorship of game journalist Raphael Lucas. It primarily tells about the problems and successes of CD PROJEKT in the development of games in The Witcher series. But there was also a place for stories about the creation of the book cycle itself, the filming of film adaptations and the formation of the Polish game master.

CHAPTER 4. THE RPG KILLER

Write, publish, create your own game, launch your franchise by selling and localizing several others. Moreover, to succeed where fate puts sticks in the wheels, and constant organizational problems put obstacles in the way. Marcin Ivinsky and Michal Kichinsky won — they released their “Witcher” on PC. The game is accompanied by a frenzied success, and their

they are called “entrepreneurs of 2008”. They take the Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year award from Poland and represent their country at an international competition. Developers who worked up a sweat, left the studio after burnout or survived a crunch lasting more than a year, probably can only laugh bitterly. It was they who worked hard to “Witcher”

It was not just a likeness of Diablo, as Michal Kichinsky dreamed at first, but a real role-playing game, largely inspired by the Gothic series. These same developers, designers and programmers gave two entrepreneurs the opportunity to create The Witcher brand, and now they are not taken into account. The pirated past of Ivinsky and Kichinsky is forgotten, no one remembers that they once sold cheap copies of games from the far West. And if someone regularly reminds Ivinsky about this, then he is only furious, but not for long.

So, The Witcher is a commercial success, and a couple of businessmen are strengthening in their decision to finally transfer CD Projekt to the rails of game development. However, everything will have to be rebuilt and redone: work on Rise of the White Wolf has exhausted the human and financial resources of the studio, and the general economic crisis has added problems. The fifty developers remaining in CD Projekt RED have dispersed on new projects (“The Witcher 2” on the Aurora Engine, “The Witcher 3” on the new engine and with an ambitious idea of an open world), but now it’s time for them to focus on a single goal again — “The Witcher 2” equipped with a new engine.

ROUGE ENGINE

“We are rebels since 2002” (“We are rebels since 2002” — Approx. trans) in white font on a red background. This slogan at the entrance to the studio echoes in the hearts of those who have been following the fate of CD Projekt RED since its ambitious debut, and does not ignore the career of the founders of the studio from the first steps in Warsaw and the sale of pirated games at giant flea markets. Do everything in your own way, by your own means. Stay as independent as possible. Today, everyone is guided by CD Projekt RED: publishers who want to improve their image adopt a policy of free content for games. The Witcher 3 Supplement or anti-DRM policy (waiver of copyright protection) the studio stands out even more from the crowd. She strives to take the production chain under full control: from the engine to dubbing. Aurora Engine gave her a chance to create a “Witcher”, launch a franchise and found a company, but a serious revision of the engine’s tools gave her much more opportunities than its creators imagined in BioWare. CD Projekt does not joke with quality. With such a philosophy, it is logical to start creating your own engine in order to control production and all internal communications between studio departments as much as possible. Tomasz Gop, senior producer, recalls: “The day we released the first part of The Witcher, we already knew that we needed to make new software. Within a year or a year and a half, programmers started writing low-level modules. And create tools based on them.” These words are confirmed by Tomek Vujcik, an engine specialist at CD Projekt RED: “Aurora is a wonderful engine, perfectly adapted for RPGs like those made by BioWare. But The Witcher is different in many ways from any BioWare game. The differences forced us to make major changes to the engine. Working on the first Witcher, we very quickly reached a point where technology limited the creativity of our designers and artists. They needed opportunities that Aurora was not so easy to supplement, and they expressed many different wishes. After finishing the development of the game, we programmers finally came to the conclusion: it will be easier to implement all these functions if we have our own engine.”

The development of the new engine was determined by three guiding principles. Firstly, it is necessary that screenwriters and quest authors can add content directly to the game without asking programmers for help every time. Secondly, it is important that games on this engine are not monsters devouring computer resources with exorbitant processor power requirements. And, finally, thirdly, it would be good if the engine supported porting to the console. As part of the first principle, tool developers spent the entire first year constantly communicating with game designers to create the necessary mechanisms, and game designers mastered the basics of the scripting language in order to learn how to program chains of events independently. “They no longer need to go to programmers, because they know the basics of the scripting language, and this is enough to write a logical block and insert it into a dialogue or into any gameplay situation. And it works! If you look logically, you do not need to know what is inside (the program. — Author’s note) to do this. In general, since we wrote the engine from the very beginning, we had the opportunity to think about how to make concept artists independent. And in the end, everything worked out.”

As for the second principle, this is already a marketing issue: one look at the technical requirements of the RPG for the PC of that time proves that “The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings” requires no less computer resources than Mass Effect 3 or Kingdom of Amalur: Reckoning. In fact, CD Projekt RED refers to existing tools that have been repeatedly tested in the development and production of modern games. These are, for example, PathEngine (movement and navigation), Havok (simulation of physical elements), Scaleform (game/player interface), FMOD (sound creation), etc. “It should be noted that we remained pragmatic at all stages of development. If a solution that met our requirements already existed, we did not develop our own. Therefore, we used middleware such as Havok for physics, Scaleform GFx for the user interface and FMOD for sound,” explains senior producer Grzesek Rdzany. Recalling this in a big article about The Witcher 2, Richard Lidbetter, an engine expert at Digital Foundry, approves of the decision to trust existing programs to create some engine functions: “This pragmatism is shared by almost all innovators in the field of gaming technology: Unreal Engine includes the same middleware, and this saves time, money and the strength of the workers.” And CD Projekt RED, as we know, is racing against time in pursuit of money and labor.

Finally, these middleware tools are also suitable for the console, which should simplify the porting process in comparison with the first “Witcher”. In fact, despite all the upgrades and improvements from CD Projekt RED, the Aurora Engine was never conceived to work on a home console. That’s why it took a few months before to ask for help from a studio where they used to work on this software. The result is known. The specter of the failure of Rise of the White Wolf was still hovering over CD Projekt RED, and it was decided that all future versions for the home console should receive the “quality seal” of RED studio, and not someone else. “We still wanted to release The Witcher on the console,” continues Tomek Vujcik, senior programmer at CDPR. — It was very difficult to do this with Aurora, an engine for PC games. We really needed something else that worked well on the console. The RED Engine development just gave us complete and unlimited control.”

In order to gain time for the production of The Witcher 2, it was quickly decided to bring the engine to mind in parallel with the development of the game. It will cost developers a couple of system failures. A few years later, Arkane Studios will make the same decision when switching from Unreal Engine (in Dishonored) to Void, a modified version of id Tech 5 from id Software (Doom) to create Dishonored 2. With the same instability, delays and the need to sometimes rewrite the code for several days so that it gives out what is expected of it. Senior producer Grzesek Rdzany remembers it all too well: “Several basic elements had to be created even before full-scale work on The Witcher 2 began. But for the most part, RED Engine was developed simultaneously with the game. This, of course, created certain difficulties due to the temporary instability of the engine, but it also allowed us to change the code to suit our goals and needs.”

Finally, if the engine becomes more powerful compared to the previous part, its capabilities also reach a new level. Artur Ganshinets recalls: “It was just a modern engine, more powerful and, most importantly, offering more advanced tools for level design and narrative design. Compared to the Aurora Engine, it was a real paradise!”.

RETHINK THE WITCHER

Armed with the best tools, RED is ready to start developing The Witcher 2. But still recall that at the very beginning of the process, the workers are still divided into two groups: on the one hand, the Witcher 2 team is still working on an improved version of the Aurora Engine, on the other hand, the Witcher 3 team is making an open world on the new engine, the same RED Engine. And there are also external DLC developments for the first “Witcher”, such as The Witcher: Outcast from roXidy studio, which was supposed to tell about Geralt’s youth and his participation in one adventure on Skelliga, or The Witcher: Scars of Betrayal from Ossian Studios. Both studios are best known for additions to Neverwinter Nights. Alan Miranda, BioWare producer and founder of Ossian, recalls: “We held a demonstration of Darkness over Daggerford at the Game Developers Conference 2007, because at the IGF (Independent Games Festival) we took the prize “Best RPG Mod”, and Marcin Ivinsky specially approached me to introduce himself. He said that BioWare recommended Ossian Studios as a good developer who knows how to work with content. Marcin was thinking about creating DLC for The Witcher (a game that will be released only in seven months) like premium mods Neverwinter Nights. We were delighted with this idea and by the end of 2007 we had already started full-fledged production of Scars of Betrayal […] CDPR needed to give players additional content that they would go through after completing the main game. […] In August 2008, Ossian and CDPR were preparing to show Scars of Betrayal at Gamescom, and then I suddenly got a call. It was the producer of The Witcher Tomasz Gop, who informed me that, unfortunately, he was canceling all external projects around The Witcher, including SoB and Outcast (which was still at the pre-production stage, as far as I know). I was shocked.” The reason for canceling these DLCs? RED is in debt. Due to the financial problems of the studio, the RED Engine project was transferred to the creation of The Witcher 2, as were all the developers of the third part. All this is happening in the middle of 2008.

First, it was decided to reduce the size of the game to make it more compact and linear. Tomasz Gop, senior producer, explains: “The first Witcher had 80 or 90 hours of play. There was a lot to do. For example, to run anywhere, because we had a lot of so-called “give-bring” quests. There are fewer missions of this type in The Witcher 2. So you run less from one point on the map to another.” However, the studio decides to add more locations that are optional for the main plot, it is better to prescribe side quests. To enrich the script, the development team uses narrative techniques from cinema and video games. First, flashbacks that repeatedly throw the hero into the past during the first, very linear hour of the game, which at the same time serves as a tutorial. Then the decisive division of the narrative into two parts in the second chapter, where the player, having made a choice, can go two different ways with specific quests. And finally, the boring third chapter, which ends too quickly.

However, in an interview for Gamasutra in 2011, Gop explains that in an RPG it is always important to find the perfect balance between the content of the game and the finances of the studio. Any developer will tell you about this dilemma. Creating additional scenes, different endings, branches in the plot — all this costs money. The more choices a player has, the more dialogues need to be written, events need to be directed, etc. Each particular player will see at the same time, maybe only a quarter or one-eighth of the entire content. During the press tour dedicated to Kingdoms of Amalur: Reckoning, we interviewed veteran game designer Ken Rolston, designer of Th e Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind, Th e Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion and tabletop role-playing games. Even then, he reminded us that RPG development is financial madness: the script must correspond not only to the options that the player chooses in the dialogues, but also to each of his actions. Now imagine that we are talking about an RPG with several character classes and different types of weapons (and each has its own action), where there are stealth missions (that is, you need to set up a shelter system and artificial intelligence) and you can use spells that change the behavior of opponents or non-player characters. So it will turn out to be an adventure where the player sees only part of the game.

By the way, the structure is more concise and linear in comparison with the first part of the game still leads the player to sixteen different endings. More precisely, to the sixteen states of the world. To quote the developers. “In the first Witcher,” explains Gop, “some cut scenes changed depending on the character who accompanied you, and the like. This is all procedural generation. So we continued to use this system in The Witcher 2. And this is one of the advantages of our own software — the game turns out to be different in terms of graphics. But I’m still sure that the main reason for creating your own engine is the opportunity to make tools that allow you to tell a story in different ways for different players. They (tools. — Author’s note) can adapt to our manner of presentation. We had dozens of ways to script the plot to make it in the form of logical blocks that can be folded into various configurations. I think this is how we were able to stand out from the mass of competitors and tell the story in our own way …”.

And to make the narrative development process in The Witcher 2 smoother, CD Projekt RED expands the team — one of the newcomers specializes in quests and is under the guidance of Konrad Tomashkevich, the tester of the first Witcher. This more even distribution of tasks indicates that the studio really plans to work at a more professional level. Recall: while working on the first part, some team members performed tasks outside their competence more than once. And often only because they were at the workplace at that moment. Has the team become more professional? Not a fact, according to Arthur Ganshinets: “I do not know what to answer to this. People were more experienced, that’s for sure. On the other hand, the main team of the first “Witcher” first struggled for resources, leading several projects at the same time, and then they were forced to unite again on one project — after that we lost the team spirit developed with such difficulty. At least, that’s how it was then in my understanding. What else can I say? A lot of new talented people on board, the organization and the entire back office seemed to function better. But is the studio capable of learning from mistakes? I don’t know.”