Mark Brown, indie developer and editor of Pocket Gamer resource, told how coding inspires the creation of non-banal puzzle games as part of the video cycle Game Maker’s Toolkit. With the author’s permission, we have prepared a printed version of the material. We share.

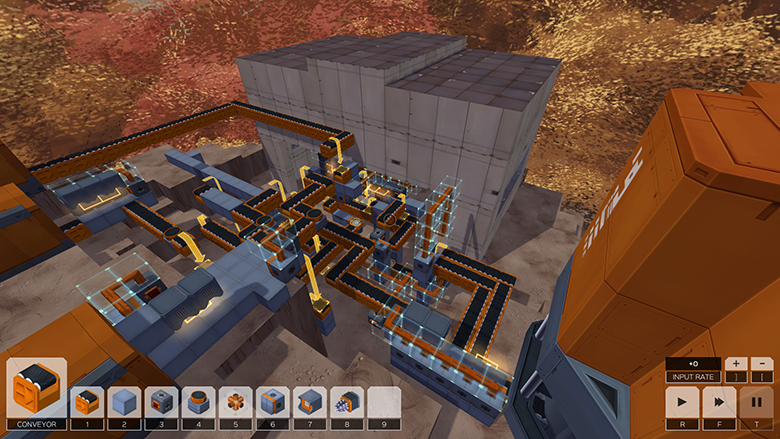

Infinifactory

Infinifactory is one of the funniest games I’ve played in the last year. And this is very good, considering that the game is not really a comedy.

To understand what I’m talking about, you first need to figure out how the game works.

At each level, you need to create a complex structure – for example, a cross-shaped thing of five parts. To do this, you need to build a conveyor that will move the blocks falling out of the wall.

These blocks are different in purpose: conveyor belts, levers, optical sensors, turn signals and welding machines. Machines for assembly are built from them.

After spending five hours, I finally managed to assemble the cruciform structure in question. But according to the assignment, it was necessary to release ten more absolutely the same ones, so that it became clear that the resulting machine was a properly functioning conveyor. So I ran it a few more times in full confidence that I would get nine perfect “crosses”.

Infinifactory

But it was not there. Instead of “crosses”, long rail-like jokes quickly climbed out of the conveyor.

Absolutely absurd. The speed of movement, like in a cartoon. My super-complicated car turned out to be so stupid that I could hardly believe it. And it was so funny that I just doubled over with laughter. Don’t cry now.

Random, unplanned comedic situations are not the only thing that differs from other puzzles of the game by Zach Barth, the creator of Infinifactory. His projects are like nothing else. Therefore, to classify them to the same genre as The Talos Principle and Snakebird means to do them a disservice.

The fact is that in these games you are trying to figure out how to solve a specific puzzle. And in Infinifactory you invent a solution.

It is no coincidence that I use the word “some”. In an ordinary puzzle, the answer is usually one. Maybe there are a couple of alternative options, or you can come up with a solution that the developer did not mean.

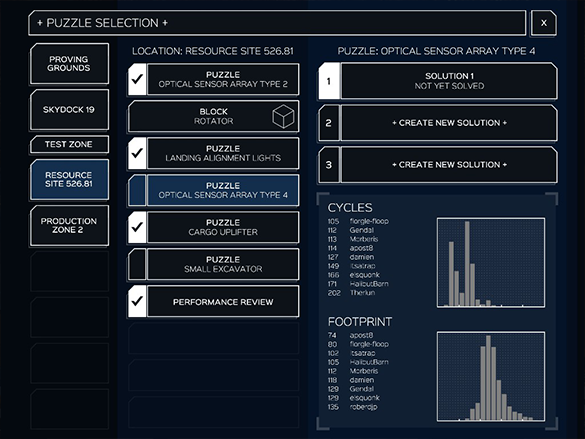

At the end of each level, the Infinifactory player is shown the following histogram

But in Infinifactory, the number of solutions is infinite. Well, almost. At least there are a lot of them.

This is evidenced by the histogram at the end of each level. It clearly shows how effective, in terms of time spent and space involved, the solution you came up with is compared to the solutions of all other players.

This infographic also highlights Zack Bart’s games among other puzzles. For example, in The Swapper it is almost useless to solve the same puzzle twice. But in Infinifactory it is very nice to return to an already completed task and come up with a more effective solution.

So it’s probably wrong to call games like Infinifactory puzzles. Their meaning is not to solve riddles, but to solve the tasks set. In such projects, you have a goal, a certain amount of materials, a limited workspace and some tools. Your task is to achieve your goal in any possible way.

Therefore, such games are not much like a riddle that you gradually guess. You rather solve problems like in the real world – you build a pipeline in Infinifactory, come up with the most optimal routes in Mini Metro, create a spaceship in the Kerbal Space Program or write code in SpaceChem.

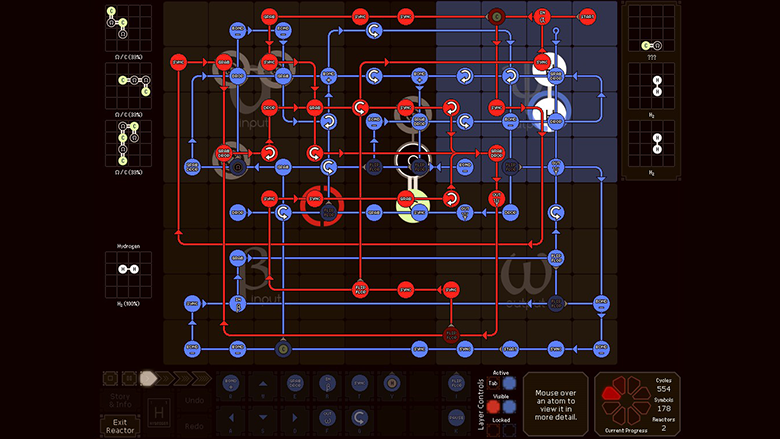

SpaceChem

By the way, SpaceChem (“Space Chemistry”) there is much more in common with programming than with chemistry: the gameplay is based on logic circuits, pre-programs and debagging.

And it’s cool for two reasons at once.

The first is programming, in fact, the best puzzle in the world. Because this is an open-ended game, it connects the imagination and makes you come up with unique solutions for incredibly complex tasks.

Second, SpaceChem shows that the game can teach you something, even if it wasn’t honed specifically for it. The project, according to the British Trade Association TIGA, was introduced into the school course in several schools in the UK.

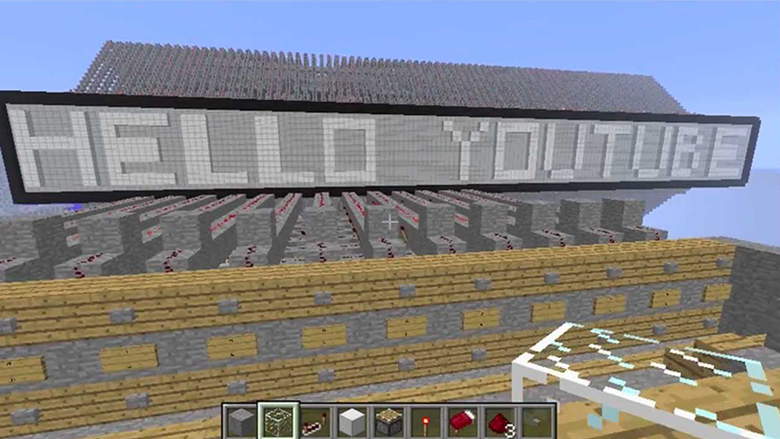

It’s the same with the redstone in Minecraft. This mineral is used as a wire in mechanical devices. With its help, many players will learn about the basics of coding. Or even not about the basics. With the help of the red stone, users managed to assemble a calculator, a graphics processor that can draw simple shapes, and a software mechanism that can play the Pachelbel Canon.

A text editor created by one of the Minecraft users

By the way, Zack Bart has a competitive Infiniminer game about block mining, from which Minecraft borrowed a lot. So Bart probably cringes every time someone says that the control in Infiniminer is like in Minecraft. Well, I guess so.

Many of Bart’s other games are also dedicated to solving problems. For example, in The Codex of Alchemical Engineering, you write programs for rotating grippers that transfer some invented minerals back and forth. In The Bureau of Steam Engineering, you connect boiler boilers with steam-powered weapons. In the almost impassable game KOHCTPYKTOP: Engineer of the People, you create integrated circuits that meet certain requirements.

And in the new TIS-100 game from Bart’s studio Zachtronics, you literally have to write assembly code. The player is even advised to print out the corresponding manual with all the necessary instructions and commands.

In my opinion, such games are part of a trend in which programmers create games about programming.

In the game Human Resource Machine from 2DBoys, you write commands for office employees so that they automatically do their job.

Human Resource Machine

And in Quadrilateral Cowboy from Blendo Games, the player needs to turn off the alarm system, open locked doors and get into well-guarded buildings, and for this he writes commands directly into a DOS-like window.

My point is that games based on real-world tasks, such as programming or engineering, can be more interesting than those in which you solve ordinary puzzles.

If you did something right, you feel a pleasant satisfaction (and if not right, then you can just laugh). In search of the most effective solution, the same tasks can be solved many times.

And, perhaps, it is easier to create levels in such games. In the SpaceChem post-mortem, Bart said that when creating the project, he simply combined interesting input and output data, checked whether the puzzle was solved or not, and then compared the levels with each other depending on the complexity.

Just don’t think that I’m calling for getting rid of traditional puzzles. The Witness, for example, is one of those games that I am waiting for the most (when the video was created, the game had not yet been released, – approx. editorial offices).

The Witness

This text is needed just to remind you that the games mentioned above are still very few. And that there are still a lot of real-world tasks that you can be inspired by when creating a new puzzle.

Translated by Irina Smirnova

Source: Mark Brown’s YouTube Blog